Will Syria’s Assad resort to violence as Suwayda protests grow?

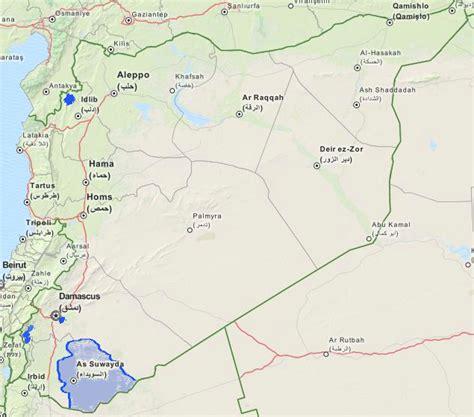

A wave of unprecedented demonstrations continued for the 11th day Wednesday in Syria’s southwest province of Suwayda, which is mainly populated by the country’s Druze minority and has remained largely neutral throughout the civil war. Thousands of protesters have been out on the streets since Aug. 20 demanding the ouster of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and ransacking the local offices of his Baath Party. Sunnis in neighboring Daraa province have joined in the calls for “bread, freedom and dignity.”

The unrest has raised fresh questions about the viability of the Syrian government, just as Arab nations are resurrecting ties with Damascus and have welcomed it back into the Arab League amid crushing sanctions imposed by European nations and the United States.

A key narrative of the regime has been that not only the Alawite sect — of which Assad is a member — is loyal to it, but the Druze and other minorities are as well. “That narrative is now collapsing,” said Joshua Landis, who heads the Middle Center of the University of Oklahoma and closely follows Syria. It has also tied Damascus’ hands.

Many believe it’s only a matter of time before government forces resort to violence, particularly if members of the security forces are targeted. “Initially, Assad probably thought ‘I have won and we can let this happen; we can let the Druze let off some steam,’” Landis told Al-Monitor. “It turned out to be a mistake from the Assad point of view, and Assad’s military will have to keep him in power.”

The Druze are Syria’s third largest religious minority, accounting for roughly 3% of its population with the rest scattered mainly across Lebanon and Israel.

The protests are the largest in the area since 2014 when Druze spiritual leaders were offended by the use of their symbols in the government’s election campaign. Further demonstrations took place in 2015 when a prominent sheikh, Wahid al-Balous — who opposed the regime and Sunni extremists fighting to overthrow it — was killed in a car bomb likely staged by Assad’s men. Protesters are carrying photos of the slain sheikh as they chant “We want Assad’s head for Balous’ blood.”

Most critically, the protests are beginning to resonate in Assad’s Alawite stronghold of Latakia, with a growing number openly criticizing the regime. “The situation is going from bad to worse. If the protests widen, they will for sure threaten the regime,” said Salih Muslim, co-chair of the Democratic Unity Party that shares power in the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and sees the Druze as natural allies. “We both want decentralization; we are both minorities. We view one another with sympathy,” Muslim told Al-Monitor.

Both groups chose neutrality throughout the conflict, with the Kurds refusing to fight the regime alongside Sunni rebels and many Druze refusing Damascus’ demands to take up arms against them. Both were targeted by the Islamic State and other Sunni extremist groups.

While Suwayda and Daraa fell back under government control in 2018, the Kurds — under the protection of an estimated 900 US Special Forces — continue to run the northeast part of the country, which is home to most of Syria’s oil and water.

In a rare show of unity, the autonomous administration’s diplomatic arm, the Syrian Democratic Council and the rival Kurdistan National Council backed by Turkey, put out statements in support of the protesters.

In Aleppo and the rebel-held province of Idlib where the Druze have faced systematic persecution, civilians are also pledging unity with Suwayda and Daraa. “It’s been that ‘unity’ that’s become a core theme of protesters on both ends of the country,” said Charles Lister, director of the Middle East Institute’s Syria project. “The idea that the original ideals of the 2011 revolution are still alive and coming back to the fore has been enough to revitalize the protest movement. It’s been remarkable to see Suwayda’s protesters expressing solidarity with Idlib ‘until we die’. That’s gotta sting in Damascus,” Lister told Al-Monitor.

The immediate trigger of the current unrest is economic hardship afflicting the country, including the sharp increase in fuel prices, the withdrawal of government subsidies and the collapse of the Syrian pound. “The Syrian economy is in a frozen state. Life is hell. Syrians can’t feed themselves nor flee. The international community has put them on an IV, saying ‘We won’t let Syria rebuild, but give it humanitarian aid so nobody starves,’” Landis said. “In Washington, people will say sanctions are working,” Landis added.

To be sure, the tone is turning determinedly political as Druze spiritual leaders traditionally aligned with the government endorse protesters’ demands — notably Hikmat al-Hijri, the most influential of the so-called Sheikh al-Aql (Sheikhs of Reason) who speak on behalf of the community to the government.

“What was triggered by economic challenges has now moved to all-out demands for regime change,” said Lara Nelson, policy director for ETANA, a nonprofit that produces extensive research on informing international policy on Syria. “The regime is really fearful of this and does not have many answers to what the people of Suwayda are demanding,” Nelson told Al-Monitor.

“It’s especially difficult for Damascus to deal with this now because they have virtually no carrots to offer — the economy is a black hole,” said Aron Lund, an international fellow for the Century Foundation. People are realizing that normalization has not led to any improvement in their daily lives. Like many, however, Lund aired doubts that the regime was in any imminent danger of falling.

Protesters’ demands include reducing commodity prices and cracking down on graft and the multibillion-dollar Captagon trade that is bankrolling the Assad regime. Worries about the moral decay fueled by the drug trade have set off alarm bells, prompting Druze women to take part in the demonstrations alongside armed Druze groups that have been blocking access to government buildings. “For Druze, preserving the social fabric is of utmost importance; it’s a red line. That is why a lot of women and religious people are protesting,” said Rami Abou Diab, a doctoral student who studies the Druze.

The presence of the Druze flag that was brandished in the day against Syria’s former Ottoman and French colonizers is symbolically significant, Diab explained, but should not be misinterpreted as a desire for independence. “What matters for Druze leaders in Lebanon and Syria is to preserve relations between Sunnis and Druze. They are careful not to become the pawns of international players,” Diab told Al-Monitor.

Unsurprisingly, Damascus is blaming Western conspirators for the upheaval and seeking to exploit divisions among the al-Aql triumvirate of sheikhs. Unlike Hijri, Sheikh Youssef Charbou opposes confrontation with the regime for fear of violent reprisals. Sheikh Hamoud al-Hanawi is hedging his bets.

In the meantime, Landis contends, the various forces that support Assad — namely Iran, Hezbollah and Russia — will “have to close ranks and come up with a plan.”

The regime has already started picking out one classic from its playbook — that of weaponizing extremist groups against minorities and then using the threat as a pretext to swoop in as it did in July 2018 when the Islamic State attacked Suwayda and killed more than 200 Druze.

“The Assad regime has a long history of colluding with extremist elements to further its interests across the country. ETANA has frequently observed this in south Syria,” said Nelson.

“ETANA has observed the movement of senior radical elements into south Syria while these protests are ongoing and is concerned that the regime might exploit or utilize the movement of these groups to further its interests in this context,” Nelson added.

Source » al-monitor.com