The Islamic State’s ideological campaign against al-Qaeda

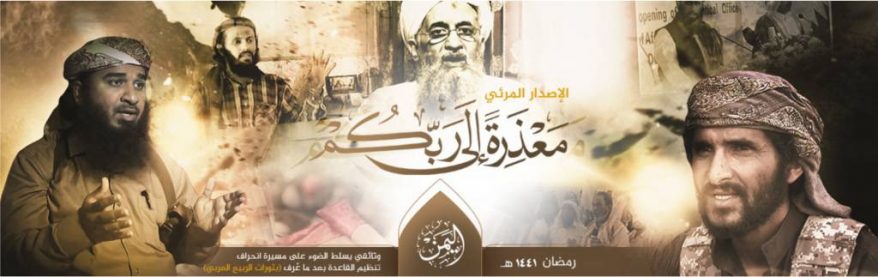

On April 29, the Islamic State’s “province” (wilayah) in Yemen released a lengthy video that is intended to undermine al-Qaeda’s ideological legitimacy within the jihadists’ ranks. The 50-plus minute production, titled “A Documentary Shedding Light on Al-Qaeda Organization’s Deviation Following What Is Known as the Arab Spring,” repeats many of the same doctrinal accusations the Islamic State has made for years.

The would-be caliphate’s ire is directed at Ayman al-Zawahiri and his lieutenants, as well as al-Qaeda’s regional branches and their allies. The Islamic State’s central charge is that al-Qaeda betrayed its own Salafi-jihadist ideology in the wake of the Arab uprisings in 2011 and 2012.

For those who have followed the Islamic State’s messaging since its rise to power in 2014, when the group mushroomed into an international menace, the allegations will be familiar.

Indeed, the group’s literature, including its Arabic weekly newsletter, Al-Naba, and its English-language magazines Dabiq and Rumiyah, have advanced the arguments discussed below on multiple occasions. Indeed, the video was highlighted in the most recent edition of Al-Naba (Issue no. 232), with an article summarizing its arguments.

Al-Qaeda’s senior leaders and the group’s regional branches are not the only ones featured in the video. The Islamic State harshly criticizes various other Salafists and Islamists, especially Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood’s men in Egypt. There are brief glimpses of Turkey’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, as well.

The former caliphate argues that all of them are insufficiently religious and have betrayed Allah’s Word. Those same figures are used mainly to impugn al-Qaeda’s own jihadist reputation, as the organization cooperated with some of those same parties, or took a lenient approach to them, during the so-called Arab Spring.

The production opens with scenes from the street protests that swept throughout the majority Arab countries in 2011 and 2012. Some of the footage shows Mohammed al-Zawahiri, the younger brother of al-Qaeda’s emir, and his comrades, including Ahmed Ashoush, leading rallies.

At first, these same men didn’t advocate or encourage acts of terrorism within Egypt, but instead preferred to use the lax security environment for the purpose of proselytization (or dawa). Al-Qaeda’s senior leadership openly advocated this lenient approach in both Egypt and Tunisia, where Islamist governments initially came to power.

Mohammed al-Zawahiri and Ahmed Ashoush at a rally in Egypt after the protests against Mubarak. This image was included in the Islamic State video.

The main target of the Islamic State’s ideological attack is Ayman al-Zawahiri. A narrator in the video charges that the elderly Egyptian al-Qaeda leader disappeared for a long stretch, thereby shifting leadership of the global network to Yemen.

Screenshots of Zawahiri’s General Guidelines for Jihad, published in 2013, are shown, with certain passages highlighted to demonstrate al-Qaeda’s alleged deviancy. In that same document, Zawahiri urged his followers to “cooperate” with “Islamic groups” when they were in agreement, while offering “advice” and working to “correct” them when the jihadists disagreed. This stood in stark contrast to the Islamic State’s own declaration of all-out hostility to the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist extremists who don’t share the jihadists’ worldview.

In conjunction with the release of the video in late April, Islamic State supporters launched a social media campaign to highlight alleged complaints by current and former AQAP members against the group’s current leadership. AQAP has suffered a series of leadership losses, including the recent killing of its overall emir, Qasim al-Raymi.

The detractors criticize AQAP’s handling of alleged spies and other security issues, while also accusing Zawahiri of being an absentee emir. The latter claim is intended to further undermine Zawahiri’s status as a global emir. It is difficult to judge how much truth there is in the critics’ claims, but the Islamic State is clearly attempting to undercut the authority of AQAP’s new leader, Khalid Batarfi.

In addition to Zawahiri, the Islamic State’s media team also critiques the role of Hossam Abdul Raouf, a veteran who has served as part of al-Qaeda’s senior management for years. Pro-al-Qaeda clerics such as Abu Qatada, Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, Hani al-Sibai and Tariq Abdelhaleem all receive condemnation in passing as well. All of these clerics have rejected the Islamic State’s caliphate claim.

The Islamic State’s pointed criticisms of Zawahiri include his allegiance to the emir of the Taliban, Haibatullah Akhundzada. Thus far, there is no evidence that Zawahiri’s oath of fealty to Akhundzada has been broken as a result of the Feb. 29 withdrawal agreement between the U.S. and the Taliban. And Zawahiri’s detractors see his ongoing allegiance to the Taliban as a significant demerit.

The anti-al-Qaeda video includes an archival clip of Zawahiri swearing allegiance to the Taliban’s emir. A narrator uses this clip to chastise al-Qaeda for implicitly endorsing the Taliban’s approach to international diplomacy. Several images of the Taliban’s “political office” in Doha are shown. The Islamic State accuses the Taliban of recognizing the United Nations charter while guaranteeing that the jihadists will not target the “Crusaders and the tyrants.”

The narrator charges al-Qaeda with blessing the Taliban’s commitment “not to fight the Crusaders,” while it directly combats the Islamic State’s Khorasan branch. The video’s editors say the Taliban fights ISIS while reassuring the “tyrants and polytheists,” maintaining good relations with the Iranians, and consorting with “apostates” in Pakistan.

On the latter score, the Islamic State’s narrator notes that the Taliban offered a glowing eulogy for General Hamid Gul, an “apostate” who was a member of Pakistan’s intelligence apparatus. Gul, who maintained close ties to jihadists, died in 2015.

An Islamic State fighter known as Abu Yusuf al-Muhajir says that despite all of this, al-Qaeda has remained loyal to the Taliban.

Some AQAP members have defected to the Islamic State’s Yemeni province, and the group clearly hopes to poach more jihadists from AQAP’s ranks. Caliphate loyalists deliver their recruiting pitch in the video. One of them, Abu Yusuf al-Qurayshi, accuses al-Qaeda of changing after the events of the Arab uprisings, when AQAP allegedly began fighting alongside the Yemeni Army.

Abu Yusuf criticizes AQAP for denouncing attacks on Houthi civilians in Sana’a, including at “rejectionist” “temples.” This reflects one difference in the two organization’s policies, as the Islamic State revels in indiscriminate attacks against Shiite civilians in multiple countries.

Al-Qaeda views such operations as too costly from the perspective of public opinion, because many Muslims reject the wanton violence.

The Islamic State has also repeatedly critiqued AQAP’s approach to state-building. In Al-Naba and other publications, the would-be caliphate has charged AQAP with being lax with respect to implementing sharia (Islamic law) throughout southern Yemen when vast parts of the territory fell under its control.

A narrator in the new video repeats that argument, saying AQAP’s front group, Ansar al-Sharia, failed to govern according to sharia in the port city of Mukalla. AQAP briefly controlled Mukalla, but the jihadists gave up control of the city as an Arab-led coalition approached in 2016.

The narrator says that Ansar al-Sharia handed over the city to local governing councils, such as the Hadhrami Domestic Council, which were allegedly endorsed by Saudi Arabia. By turning over control to local entities, the narrator claims, AQAP failed to enforce the jihadists’ puritanical religious code and allowed “polytheistic” worship to remain in place.

Another Islamic State fighter, a man known as Abu Abdallah, claims to have witnessed AQAP’s shortcomings in Mukalla. Abu Abdallah, a former AQAP member, blasts his one-time comrades for failing to live up to their purported desire to impose sharia.

His testimony is used to frame archival footage of AQAP’s first emir, Nasir al-Wuhayshi, who explainied why al-Qaeda has taken a deliberate, staged approach to Islamic governance. For Wuhayshi and al-Qaeda’s other leaders, the Muslim population has lived under secular governance for decades and doesn’t understand how to live according to sharia.

Therefore, AQAP’s men reasoned, people should be gradually indoctrinated, such that they don’t reflexively reject the jihadists’ governance. In contrast, the Islamic State has no patience for al-Qaeda’s cautious transformation.

An Islamic State witness, Abu Yusuf al-Muhajir, argues that the people were let down and “deceived” by AQAP’s incremental approach. The Yemeni people were supposedly waiting for “Allah’s sharia” to be implemented “in the land,” but AQAP chose to stick with tribal customs.

There is a tension in the Islamic State’s argument. Namely, if the people were demanding the jihadists’ version of sharia, as the Islamic State claims, then AQAP wouldn’t have found it necessary to slowly implement it. One of AQAP’s central missions inside Yemen is to build an Islamic emirate. That mission is not close to fruition today, but AQAP has seized group in southern Yemen twice in an attempt to lay the groundwork for its new state.

The Islamic State’s new video takes aim at AQAP’s ideological leadership across al-Qaeda’s global network. For instance, one scene critiques AQAP theologians and other al-Qaeda figures for denouncing the Islamic State’s expansion in the Caucasus region.

Two leading AQAP clerics, Harith bin Ghazi al Nadhari and Ibrahim Rubaish, both of whom were killed in drone strikes in 2015, organized a campaign to reject the caliphate’s attempt to undermine the Islamic Caucasus Emirate (ICE), which was affiliated with al-Qaeda. Their campaign wasn’t very successful, but the Islamic State hasn’t forgotten it. Both al-Nadhari and Rubaish are shown in a negative light in the video.

AQAP isn’t the only al-Qaeda branch to come under rhetorical fire. The Islamic State’s men object to the policies followed Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), too.

The Islamic State’s Abu Yusuf al-Qurayshi claims that some parties are hiding nationalist, tribal and even democratic goals beneath their religious calls. Abu Yusuf compares their attitudes to the pre-Islamic period of jahiliyyah, or ignorance.

He points to al-Qaeda’s “branch in Mali” to illustrate his point, saying that al-Qaeda’s men have been allied with “apostate” and secular movements there. This is a reference to the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad and other Tuareg parties, as AQIM and its own subsidiaries cooperated with these groups during their takeover of Mali in 2012.

AQIM’s emir, Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud (a.k.a. Abdulmalek Droukdel), is also heavily criticized in the production, as are other figures in his organization. The so-called caliphate’s media team uses archival clips of Wadoud and Adam Gadahn, a spokesman who served Osama bin Laden, to argue that al-Qaeda stopped fighting tyrants throughout North and West Africa.

“I would like to affirm…that Al-Qaeda Organization hasn’t posed and won’t pose a threat to Mali, nor to neighboring states, nor to Africans as France falsely claims,” Wadoud says in an old clip recirculated in the video. “Al Qaeda and the groups allied with it, have nothing to do with fighting the Libyan state, nor any other Libyan party after the Qaddafi regime, and they have no interest in any such fight,” Gadahn, who was killed in a 2015 drone strike, says in another clip.

The speeches by Wadoud and Gadahn were made in the wake of the Arab uprisings and reflected al-Qaeda’s priority at the time – namely, overthrowing the dictatorships rocked by the protests. However, that was not al-Qaeda’s policy in the years thereafter. For instance, al-Qaeda’s branch in West Africa, the Group for Support of Islam and Muslims (or JNIM), regularly attacks the Malian government in addition to other local forces, as well as the French.

Still, the Islamic State is keen to selectively use Wadoud’s and Gadahn’s words against al-Qaeda, making it seem as if the group has abandoned the fight against regional governments forevermore.

The Islamic State’s predecessor organization in Iraq was confronted by the Sahwa (awakening movement), which consisted of tribesmen and other parties opposed to the group’s authoritarian rule. For years now, the Islamic State has branded all of its opponents as awakening groups, charging that al-Qaeda is in cahoots with them. The new video repeats that allegation once again, as al-Qaeda has worked with parties everywhere from eastern Syria to Libya to oppose the Islamic State.

One of the Islamic State’s witnesses, Abu Yusuf al-Qurayshi, employs this motif in his criticism of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which was formerly known as Al-Nusrah Front. Al-Qurayshi accuses HTS of being allied with both the “awakenings” and Turkey. The video’s editors include footage of HTS leader Abu Muhammad al-Julani explaining that he and his men consider other factions to be Muslim, even if their members make theological or other mistakes.

The Islamic State ties this critique to AQAP itself. At one point, an audio clip of Qasim al-Raymi (who was the emir of AQAP until his demise in January) praising Jaysh al-Fath is played. Jaysh al-Fath was a coalition in Syria that included Al-Nusrah Front, Islamist groups and others.

The joint venture swept through the northwestern Idlib province in 2015 and al-Raymi praises its successes in the archival clip. The Islamic State points out that some of Jaysh al-Fath’s members have praised Erdogan, including upon his re-election as Turkey’s president.

For the Islamic State’s al-Qurayshi, the point is that the insurgents in Idlib now live under Turkey’s protection and not according to Allah’s sharia. Therefore, the Islamic State charges that al-Qaeda and its offshoots (including HTS, which claims to be independent) have compromised on their beliefs in Syria and elsewhere.

The video includes images of other extremists who have opposed the Islamic State in Syria and Libya. Some of the scenes include footage of Ahrar al-Sham and its late leader Hassan Abboud. (The Islamic State is thought to have killed Abboud’s mentor, Abu Khald al-Suri, in early 2014. Al-Suri is a known al-Qaeda figure.) Sheikh Abu-al Fath al-Farghali, an ideologue in HTS, is shown, as is Sheikh Abdullah al-Muhaysini, a U.S.-designated terrorist. Still other current and deceased Syrian opposition figures are put in the Islamic State’s ideological crosshairs.

Outside of Syria, the Islamic State extends this critique to figures such as Abdelhakim Belhadj, a former senior leader in the al-Qaeda-linked Libyan Islamic Fighting Group. Belhadj is briefly seen early on in the video.

It is noteworthy that the organization’s media apparatus is emphasizing these arguments against al-Qaeda once again. It shows that the Islamic State, despite suffering significant setbacks, has a deep institutional memory.

The video’s narrator and witnesses recount events that took place years ago, critiquing al-Qaeda’s post-2011 documents, official statements and actions. Indeed, the video includes a montage of various al-Qaeda texts and statements, with an examination of key lines. From the jihadists’ perspective, this document review highlights the fundamental theological and strategic issues at stake.

Whoever produced the video clearly remembers the caliphate’s version of the story well, as many of the details covered first became a part of the Islamic State-al-Qaeda rivalry in 2014 and 2015. This demonstrates that the self-declared caliphate has developed a significant institutional hatred for al-Qaeda – an intense dislike that hasn’t subsided during years of infighting. While it is always possible that some factions within each group are currently working together, or they will do so in the future. But the video indicates that a grand reconciliation between the two jihadist rivals is unlikely in the near future.

In fact, the Islamic State continues to sow discord within al-Qaeda’s ranks, poaching commanders and fighters who don’t approve of Zawahiri’s approach to the political turmoil unleashed by the Arab protests and their aftermath. The Islamic State witnesses interviewed in the production directly call upon their former AQAP brethren to defect – a message that doesn’t speak to impending unity.

Source: Long War Journal

You must be logged in to post a comment.