The Big Problem With Iran’s Strategy in the Middle East: It Works

No doubt about it: The Israel-Hamas War has radically altered the trajectory of the Middle East’s politics and injected a level of volatility into developments not seen in decades. The conflict marks not only a new phase in a century-long conflict between Jews and Palestinians, but one more chapter in Iran’s 45-year shadow war against the United States, Israel, and their allies in the region.

Over the long course of the shadow war Tehran’s objectives and its strategy for reaching them have been remarkably consistent. Its chief foreign policy goals since the formation of the Islamic Republic in 1979 have been forcing the United States out of the region and preventing Israel from normalizing relations with its neighbors by inciting chaos, violence, and deep-seated resentments. A leading scholar of the U.S.-Iran conflict, Suzanne Moloney of the Brookings Institution, points out that Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, in power since 1989, “has never wavered in his feverish antagonism toward Israel and the United States. He and those around him are profoundly convinced of American immorality, greed, and wickedness; they revile Israel and clamor for its destruction, as part of the ultimate triumph of Islamic world over what they see as a declining West and an illegitimate ‘Zionist entity.’”

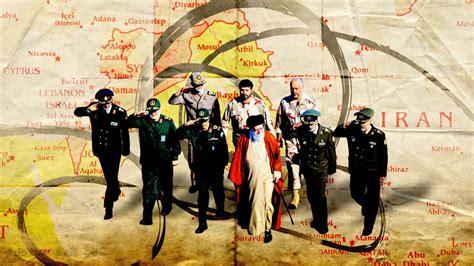

Tehran’s primary method for pursuing these ends is a unique protracted war strategy that combines political mobilization, coercive diplomacy, and information warfare with offensive military operations conducted by a formidable array of proxy forces—most of them composed of Shia militia groups—which Iran calls the Axis of Resistance.

More than a dozen armed groups in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and Lebanon form a loose network of more than 150,000 proxy warriors who have their own interests but share a commitment to challenging American hegemony in the region. Their tactics are hardly unique. They employ the usual grab bag of irregular warfare tactics including traditional terrorism, assassination, suicide bombing and rocket attacks. Hamas in the Gaza Strip is a core member of a network that began in Lebanon in the early 1980s with Hezbollah and expanded to include Kataib Hezbollah in Iraq and the Houthis in Yemen, among others.

The first thing that must to be said about Iran’s strategy is that it has been remarkably effective, especially since the beginning of America’s War on Terror. Since that time, Tehran has shown itself to be far more strategically dexterous than Washington. Nowhere is that success more palpable than in Iraq, where Iran-backed militias of varying size and skill helped to force the United States to withdraw virtually all its forces by 2011. Today, Iraqi politics are far more heavily influenced by pro-Iranian political factions and personalities. Without question, Iran was the major strategic beneficiary of the Iraq War.

Although the U.S. government has placed dozens and dozens of sanctions on Iran’s proxy forces throughout the region beginning as far back as 1995, the network today is better funded and far more militarily capable than it was back in the early years of the Iraq War. The spectacular success of Hamas’ Oct. 7 surprise attack demonstrates this reality dramatically. And of course, as Suzanne Maloney observes, “it is inconceivable that Hamas undertook an attack of this magnitude without some foreknowledge and affirmative support from Iran’s leadership. And now Iranian officials and media are exulting in the brutality unleashed on Israeli civilians and embracing the expectation that the Hamas offensive will bring about Israel’s demise.”

Thus far, the Israel-Hamas War has only enhanced Iran’s geopolitical position, for the conflict has brought immense international pressure on Israel to accept a demilitarized Palestinian state as the only viable solution to the current travails. The advent of the war brought an abrupt end to the U.S-led effort to secure a long sought-after formal alliance between Israel and Saudi Arabia—a powerful adversary of Iran.

The war constitutes a strategic setback for Washington in that it must now divert military and diplomatic resources it has hoped to use to counter a rising China in the Indo- Pacific to the Middle East.

The public line from Tehran is that its proxy network has been conducting attacks on U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria and the Red Sea with a view to pressuring Israel and America into a ceasefire in Gaza, at which point they will cease.

This is nothing short of dissembling on the part of the Islamic Republic. The Palestinians’ fate is of little strategic concern to Ayatollah Khamenei and his minions. Tehran continues to focus on its overarching objective of stirring up trouble and chaos to frustrate America’s effort to shape the region’s geopolitical affairs. Afshon Ostovar, associate professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey and one of America’s leading experts on Iranian foreign policy, puts it this way: “For Iran, this is a long war not a short war, and this has nothing to do with Gaza.” It is “about Iran’s steady, long march across the Middle East to push out U.S. forces and weaken U.S. allies.”

There is no question that Iran does not exercise formal command and control over this impressive array of irregular fighters. Rather, Iran’s elite Quds force—in essence the special forces of the Revolutionary Guard Corps—establishes close cooperative relations with each group’s leadership, offering them the same sort of incentives and resources that U.S. Special Forces offered irregular forces in Iraq and Afghanistan: funding, tactical and operational advice, advanced weaponry, and access to excellent intelligence. Tehran has been able to use these forces repeatedly and escape serious retribution on the grounds that the groups make their own operational decisions.

In truth, Iran’s strategy against U.S. interests bears similarity to the protracted warfare strategy that served both the Vietcong and the Taliban so well: keep the tempo of operations low, conduct extensive and exhaustive political warfare to shape the narrative of conflict, and keep conflict bubbling on a low boil in several places at once.

Tehran’s response to the recent American airstrikes against the proxy forces has been notably muted and restrained. That’s not surprising to Iran watchers. Ayatollah Khamenei does not in any sense want a conventional conflict with the United States. Nothing would be gained for Iran in that sort of conflict, and much to be lost, including perhaps its quasi-covert nuclear weapons development program.

Iran’s conventional military capabilities on land, sea and air are limited and trifling to those of the United States. After a U.S. frigate was struck by an Iranian mine in the Persian Gulf in April 1988 the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps destroyed half the naval forces of Iran in a single day in Operation Praying Mantis. The gap between American and Iranian conventional military power has only grown wider since the late 1980s.

The Iranian leadership, says Ostovar, “hope to ensnare the United States into an unwinnable situation, one that eventually may prompt Washington to see more value in simply walking away from its military commitments in the region rather than obligating more resources to preserve the status quo.”

Much of Iran’s considerable foreign policy success is clearly down to the sheer strategic acumen of Khamenei and his key foreign policy advisers. The Ayatollah has been in power longer than any other leader in the region. According to two leading scholars of Iran’s foreign policy, Khamenei has “an uncanny ability to blend militancy and caution… He understands the weaknesses and the strengths of his homeland when he seeks to advance the Islamic Revolution beyond his borders.”

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for America’s leading foreign policy decision-makers regarding the Middle East. Indeed, enduring problems for Washington in the region have been an overreliance on military force and an inability to integrate military operations with a truly viable political message and strategy.

It seems clear indeed that Washington will have many opportunities in the coming months to sharpen up its game.

Source » yahoo.com