Terrorist prisoners study psychology to fool rehab professionals

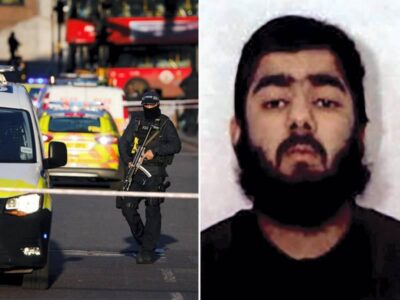

Terrorist prisoners across Europe, such as London Bridge attacker Usman Khan, are hiding in plain sight and deceiving deradicalisation professionals, a study has found.

The Counter Extremism Project think tank is calling for “significant improvements” in rehabilitation schemes after it found some terrorists were studying psychology to bluff professionals into believing they no longer pose a threat.

In its study released on Tuesday, the think tank makes 13 recommendations for dealing with extremist prisoners, including the use of lie detectors, and is calling on European nations to follow the UK in ending automatic early release for prisoners convicted of terrorism.

It advises that extremists should have limited contact with each other in prison to avoid them exploiting the system.

Report author, Ian Acheson, recommends creating a unified team with permanent overall responsibility for offenders to prevent dangerous extremists from “falling through the net”.

“One unified, multidisciplinary team with executive authority would better ensure coherence and continuity in offender risk management, thereby reducing handovers and rationalising the dangerous sprawl of the terrorist offender threat response,” it says.

“These new arrangements, combining stable and long-term relationship-building with assertive intervention, would make disguised compliance harder to sustain.”

It cites the case of Usman Khan, who having been released halfway through a prison sentence for plotting to blow up the London Stock Exchange killed two people at a rehabilitation event after conning those monitoring him.

“While Khan was released with 16 separate licence conditions and the highest level of multiagency public protection arrangements, he still managed to create a positive and enduring image of a reformed citizen in the minds of those who worked with him,” the report says.

“This undoubtedly had an impact on decisions to allow him to travel to and attend the public function unsupervised, despite still being regarded as high-risk. Indeed, a UK inquest into his victims’ deaths in April 2021 reveals that while in prison, Khan was one of the main extremists responsible for radicalising others in his wing.”

Vienna attacker, Kujtim Fejzulai, murdered four people in November 2020 and injured more than 20 others after being released early from a jail sentence for terrorism after undergoing a deradicalisation programme.

“The perpetrator managed to fool the deradicalisation programme of the justice system, to fool the people in it and to get an early release through this,” Austria’s Interior Minister, Karl Nehammer, said at the time.

Convicted terrorist Sudesh Amman was also under special police surveillance when he stabbed two people in Streatham, south London, in February 2020.

Released from prison the previous week after serving part of a three-year sentence for terrorist-related activities, he was also deemed a sufficiently high risk to require close monitoring.

The report says that many violent extremists consider detention “as a test of their commitment to their cause”.

“During their sentence, they look for ways to convince those with whom they interact, eg, prison officers, social workers, psychologists, that they have understood the error of their ways and have turned over a new leaf to speed up their release.”

It says some convicted terrorists had opted to study psychology and while that “could be perceived as a positive step forward, experts allege that in many cases they use what they learn to better manipulate the work of prison therapists”.

The authors argue for a more assertive and tailored approach to establishing the authenticity of jailed terrorists and the report calls for “sense-checking” of extremists “by a team of practitioners surrounding the individual”.

“The stakes are far too high for a failure in identifying those still wedded to violent extremism,” it says.

“Violent extremists’ short-term exposure to therapists seems an unlikely way to foster an authentic and sustainable new identity in environments as fragile and abnormal as prisons.

“These complexities and risks suggest an approach that should be longer, more individualised, more intrusive and more sceptical than the current fashion for short-term metered ‘doses’ of generic intervention.”

Source: The National News