Taliban commander who launched deadly bombings in Kabul is now a police chief in charge of security

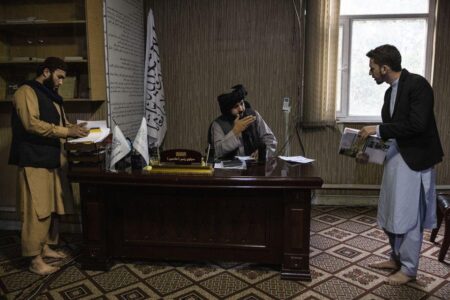

Mutmaeen used to run Taliban suicide-bombing squads in Kabul. On a recent day, in his new role as police chief for one of the Afghan capital’s districts, he was busy mediating a marital dispute.

A woman clad in a burqa complained she could no longer live with her interfering mother-in-law. Clearly used to being in command, Mr. Mutmaeen lectured the husband that under Islamic law he must provide his wife with “shelter and other basic necessities.”

Mr. Mutmaeen’s solution was to have the mother relocate to the home of her other son. After some persuading, the husband reluctantly agreed.

His face framed by a black turban and black beard, Mr. Mutmaeen didn’t see the jarring change from his previous occupation as remarkable. In the past, Americans and locals who worked with them were legitimate targets as the Taliban sought to create a true Islamic order, he said. Today, he reasoned, community policing serves the same goal.

“Previously I was serving Islam, and now I’m also serving Islam. There is no difference,” Mr. Mutmaeen, 39, said.

The Taliban-turned-cops under Mr. Mutmaeen’s command aren’t being paid, and they haven’t received training in actual police work. It isn’t clear what laws they are enforcing, other than their understanding of the Islamic Sharia.

The penal code of the U.S.-backed Afghan republic, deposed by the Taliban on Aug. 15, may or may not be in force. The Taliban have said they aim to bring back the 1964 constitution from the era of King Zahir Shah—minus unspecified clauses they see as contradicting Islam.

The same haphazard approach permeates the rest of Afghanistan’s government bureaucracy, where thousands of educated professionals abandoned their jobs or left the country in August. The Taliban appointed Islamic clerics with little management experience to run ministries and government departments. As of this month, the country’s electric utility company, which hasn’t paid its foreign power suppliers or collected much revenue at home since Aug. 15, is headed by a mullah.

With Afghanistan’s harsh winter approaching and economic activity paralyzed after the banking system seized up in August, challenges are mounting.

“There is no indication that the Taliban has any idea how to run a country,” said Asfandyar Mir, a senior expert at the United States Institute of Peace, a bipartisan federal institution established by Congress and based in Washington.

Even the Taliban’s main strength—providing security—is being tested by a ferocious campaign of attacks by the regional affiliate of the Islamic State militant group, including two bombings this month at mosques used by the minority Shiite Muslims, which killed dozens.

At Kabul’s new primary court, housed in the former ministry of public works, no trials are taking place, according to court staff. Instead, the court is hosting mediation to resolve disputes. If the parties can’t reach a compromise, a case file is prepared for a future hearing before a judge.

The Taliban ran shadow courts in areas they controlled before seizing power. A 2020 study by the Overseas Development Institute, a think tank in London that does research on global inequality, found many locals believed these Taliban courts delivered swifter, fairer and less-corrupt justice than the U.S-backed government system.

Sharia law, which derives from the Quran and the sayings and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad, covers both criminal and civil cases, as well as moral conduct. It has harsh penalties for some misdemeanors, including whipping for adultery and cutting off a hand for theft.

The Taliban gained notoriety for applying these punishments when they were last in power, between 1996 and 2001. Most Muslim-majority countries today don’t carry them out.

Source: Quebec Tribune