How secret schools for girls are teaching under the Taliban’s nose

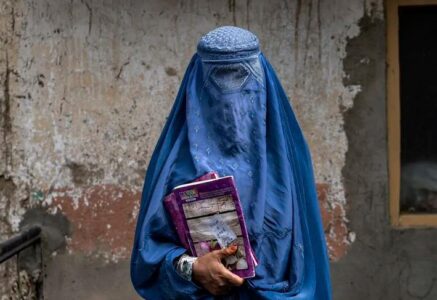

In the morning, Shogofa covers herself head to toe with a burqa and heads to school.

As she makes her way, she tries to ensure that no one sees her supplies.

After all, the school she’s going to is a secret.

The 16-year-old once went to public school with the dream of becoming a journalist. But the return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan saw a ban return on girls going to secondary school or studying journalism.

Shogofa, not her real name, travels the Kabul roads every day in fear of spies for the Taliban, a group with a record of torturing and putting women activists into prison.

“There is such fear that I think everyone is looking for me and I have to be careful,” she says.

It has been more than a year since the closure of girls’ secondary schools in Afghanistan under the rule of the Taliban, a decision sometimes attributed to Islam and sometimes to Afghan culture.

But girls have not stopped trying to learn, and women have established secret schools to educate a generation. It’s a daring decision.

Although there are no accurate statistics, in big cities like Herat and Kabul, a number of young women have set up secret schools to teach girls.

Shogofa speaks as if she has suffered great pain.

When asked “what do you want from the Taliban?” Shogofa replies “nothing.”

“We do not have any demands from them, because they lie, they did not come to (power through) the people’s vote and occupied our country by force,” she tells the Star, speaking in Persian. “The action of the Taliban is neither Islamic nor cultural, but primitive.”

“We ask the international community to put pressure on the Taliban, and not legitimize a terrorist regime by smoothing the red carpet under their feet and sending weekly bags of money to them.”

Bahar is a math teacher at Shogofa’s school in the capital. Bahar (the Star is not using her real name) was a third-semester student in administration and business at Kabul University.

She says initially, after the Taliban’s decision to close girls’ schools, she felt helpless and desperate, but hung on to some hope. Bahar and some other friends decided to provide a secret place for girls’ education.

It hardly looks like a school — a room with a carpet and few chairs, a whiteboard and some markers.

Three days a week, she and her colleagues wait for 15 female students. They start their classes at 10 every morning and continue until noon. They check each student from the back window, then open the door to let them in.

“There are many other girls who want to attend this school, but due to the lack of space and resources, as well as the need to hide, our efforts have been limited,” Bahar says in an interview.

“It has been four months since my colleagues and I created these secret classes. We hold a class for one to two hours a day, focusing on mathematics, biology and physics,” she adds.

She says their school has 40 students of different ages with three teachers who are volunteers.

“Our work is like playing with death, but we accepted this challenge because of our generation. We know that the Taliban regime will end one day, so there should be girls who learned formal lessons to go forward and enter formal school, and then university.”

Bahar says they got the idea for the school from the previous Taliban regime, in 1996-2001. She says that they get a small amount of money from the girls’ fees and spend it on their education.

Nazanin (not her real name) is another student of this Kabul school. The 16-year-old had great ambitions last year before the Taliban regained control.

Nazanin says that if the government schools were open, she would be in Grade 11 now.

“Everything crashed, thousands of other girls deprived of their basic right,” Nazanin says.

“When the schools closed, I lost hope and now that I come here, I feel happy (to study difficult subjects). But when I see girls who don’t have the same opportunity, I get very disappointed.”

After the Taliban decided to keep the gates of secondary schools closed to female students, a large number of female activists have tried to establish online classes.

But Homeira Qaderi, a Fellow at Harvard University and former adviser to the Afghan Ministry of Education, considers this kind of secret education to mean the removal of women from society and says that no secret education can replace formal schools.

She says girls are still deprived of the path to higher education, and cannot pass the university entrance exams.

“Secret educations can help girls from a psychological point of view, but from the logical point of view, these schools are not the answer to today’s conditions,” Qaderi says via WhatsApp.

The Taliban have given different reasons for the closure of girls’ schools. Initially, the declared reason was religious, but after domestic and international pressure, they said the clothes of female students should be in accordance with Islam, a reason that carried little logic.

Later, they stated the reason was cultural and implied that the Pashtuns — the people who predominate in the south and east and from whose ranks most of the Taliban come — do not want adult girls to go to school. It’s not clear this is actually the case.

The closures are affecting international relations. Western officials have explicitly said that the progress on women’s rights and the schools’ opening are a key factor in bringing the Taliban closer to the billions of dollars that are blocked in the United States.

A senior Taliban diplomat in a neighbouring country who does not want his name published says closing girls’ schools isn’t mandated by Islam. He admits that the daughters of most of the Taliban leaders, including his own daughter, go to school and university outside Afghanistan.

He says his daughter attends school every day, observing all Islamic values, travelling by girls’ school bus. Asked if the driver is a woman, he laughs. “He is an old man.”

Source: Thestar