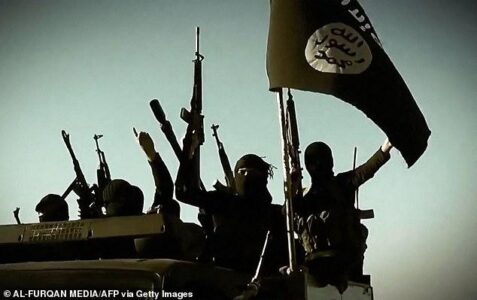

Repatriations Lag for Foreigners with Alleged ISIS Ties

More than 42,400 foreigners accused of Islamic State (ISIS) links remain abandoned by their countries in camps and prisons in northeast Syria despite increased repatriations of women and children in recent months, Human Rights Watch said today. Kurdish-led authorities are holding the detainees, most of them children, along with 23,200 Syrians in life-threatening conditions.

Recent Turkish air and artillery strikes have compounded the danger. But even before Turkey’s attacks, at least 42 people had been killed during 2022 in al-Hol, the largest camp, some by ISIS loyalists. Hundreds of others were killed in an attempted ISIS prison break in January. Children have drowned in sewage pits, died in tent fires, and been run over by water trucks, and hundreds have died from treatable illnesses, staff, aid workers, and detainees said.

“Turkey’s attacks highlight the urgent need for all governments to help end the unlawful detention of their nationals in northeast Syria, allowing all to come home and prosecuting adults as warranted,” said Letta Tayler, associate crisis and conflict director at Human Rights Watch. “For every person brought home, about seven remain in unconscionable conditions, and most are children.”

Turkish air strikes since November 20 targeting the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the region’s armed force, struck perilously close to al-Hol camp and Cherkin prison, which together hold thousands of the detainees. The strikes, which reportedly killed eight guards, temporarily cut off power, stopped water, fuel, and bread deliveries, and reduced already limited medical and other services in al-Hol and Roj, a smaller detention camp, detainees, relatives, and aid and family groups told Human Rights Watch.

During a trip to northeast Syria in May 2022 and subsequent calls and text messages, Human Rights Watch interviewed 63 foreign ISIS suspects and family members in camps, prisons, and other detention centers. Human Rights Watch also spoke with 44 camp and detention center administrators and staff, aid workers, foreign government officials, and relatives in detainees’ countries of origin.

Medical care, clean water, shelter, and education and recreation for children were grossly inadequate, Human Rights Watch found. Mothers said they hid their children in their tents to protect them from sexual predators, camp guards, and ISIS recruiters and killers.

In Roj, six women said guards had transferred them to detention centers for weeks or months, in some cases physically abusing them and leaving their children to fend for themselves. Boys and their mothers said guards had forcibly disappeared adolescent boys from the camps and placed them in detention centers, where they lost contact with relatives for months or years.

In al-Hol, an Iraqi man said that ISIS loyalists killed several of his close relatives in the camp in 2022, calling them “spies.” Then, he said, “they left me a [written] message with a knife struck through it: ‘Allahu Akbar [God is greatest], the Islamic State remains. Your slaughter is near.’”

In Roj, a woman said guards held her for days in early 2022 in a toilet stall where they interrogated her and subjected her to electric shocks, accusing her of involvement in a camp protest. “I kept telling them I wasn’t involved, but they kept torturing me,” she said.

In Alaya prison, a wounded French teen whom guards snatched from his family and placed in a crowded cell for 23 hours a day pleaded for care for his disabled arm but said that most of all, “I just want to see my mother.”

The foreigners come from about 60 countries. Most were rounded up by the SDF, a Kurdish-led, US-backed regional armed force, when it routed ISIS from its last physical holdout in Syria in early 2019.

None of the foreigners have been brought before a judicial authority in northeast Syria to determine the necessity and legality of their detention, making their captivity arbitrary and unlawful. Detention based solely on family ties amounts to collective punishment, a war crime.

The foreigners are held in northeast Syria with the tacit or explicit consent of their countries of nationality. Some countries, such as the United Kingdom and Denmark, have revoked the citizenship of many or some of their nationals, leaving several stateless in violation of their right to a nationality.

Governments that knowingly and significantly contribute to this abusive confinement may be complicit in the foreigners’ unlawful detention, Human Rights Watch said. Unlawful detention committed as part of a widespread or systematic “attack directed against any civilian population,” meaning a state or organizational policy to detain people unlawfully, can amount to a crime against humanity.

Since 2019, at least 34 countries have repatriated or allowed home more than 6,000 foreigners, including nearly 4,000 to neighboring Iraq, according to figures from the Administration of North and East Syria, the region’s governing body, and other contacts. Repatriations increased in 2022 with more than 3,100 foreigners taken home as of December 12, the Autonomous Administration said. Since October, at least eight countries have brought nationals home: 659 to Iraq, 17 to Australia, 4 to Canada, 58 to France, 12 to Germany, 40 to the Netherlands, 38 to Russia, and 2 to the UK. In November, Spain said it would repatriate at least 16 nationals by year’s end. Most countries have brought back few, if any, men. Many repatriated children are successfully reintegrating in their home countries, Human Rights Watch found.

In a written response to Human Rights Watch requests for comment on the detainees’ treatment, the Autonomous Administration said it was trying its best to uphold human rights law. “This does not mean that there are no mistakes here and there on the level of individuals or some small groups within the military forces,” it added. The Autonomous Administration “takes into account” any reports of detainee abuse, it said.

The Autonomous Administration has repeatedly urged governments to repatriate their nationals and in the meantime to increase aid to ensure the detainees’ humane treatment. They have also called on governments to help regional authorities prosecute foreign ISIS suspects. “It is very difficult for us to carry this burden on our own,” Abdulkarim Omar, the administration’s European envoy and former foreign relations co-chair, told Human Rights Watch.

The United States and the UK, members of the Global Coalition Against ISIS, have spent millions of dollars on prisons to hold the detainees in northeast Syria. But foreign governments have not taken steps to provide the detainees with judicial review.

“While better conditions are essential, indefinite detention without judicial review is unlawful even in the best of prisons,” Tayler said. “Countries risk complicity in this abuse if they enable detentions that violate basic rights or that create direct or indirect obstacles to their nationals’ returns.”

Security Concerns

Governments that have stalled on taking back their nationals cite security concerns and public backlash. In addition, officials from five governments with nationals detained in northeast Syria have told Human Rights Watch that the authorities there had at times set repatriation conditions that compounded the already challenging task of extracting their nationals.

But top United Nations and US officials have urged countries to repatriate their nationals, saying the detainees represent a greater threat if left in northeast Syria, where hardliners among them could escape, particularly while the SDF is diverted to responding to Turkey’s attacks, and children could be vulnerable to recruitment. The US, which leads the 85-member Global Coalition Against ISIS and has brought back 39 nationals – nearly all its citizens detained in the region – has helped several countries extract their nationals for repatriation.

At the same time, the US military was spending $155 million in 2022 and requested $183 million for 2023 to train, equip, and pay thousands of SDF and Asayish, a regional security force that also guards the detainees. The US is also using the funds to increase security at al-Hol camp and to build a new prison in the town of Rumaylan and refurbish at least three existing detention centers, including for boys.

The detention centers are a stop-gap effort pending repatriations to “improve the SDF’s ability to securely and humanely” detain the ISIS suspects, the US Department of Defense told Human Rights Watch. They also will improve conditions for those who at risk of serious harm if they were sent home, according to the department’s reports. Several thousand detainees come from countries with records of counterterrorism abuse.

The UK, which has taken back 11 nationals but left an estimated 60 others, has spent at least $20 million on a new prison called Panorama for the detainees in al-Hasakah.

The Detainees and Places of Detention

As of December 12, the SDF and Asayish were holding roughly 65,600 men, women, and children as ISIS suspects and family members in camps, prisons, and other detention centers in northeast Syria, according to the Autonomous Administration and US government figures.

More than 37,400 foreigners, including more than 27,300 Iraqis, are detained in al-Hol and Roj camps. Nearly two-thirds of foreign camp detainees are children, most under age 12. Nearly one-third are women. The camps also hold about 18,200 Syrian men, women and children whose conditions are dire although they have more freedom of movement than the foreigners.

The SDF is also holding about 10,000 men and boys in prisons and makeshift detention centers –about 5,000 Syrians, 3,000 Iraqis and 2,000 from more than 20 other countries, according to the US Department of Defense and other sources. They include as many 700 Syrian and foreign boys, four sources with knowledge of the facilities estimated, and hundreds of young men held since they were children, according to the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria. Humanitarian access to these detention centers is highly restricted.

At least 180 other foreign boys are estimated to be locked in detention facilities that regional authorities inaccurately describe as “rehabilitation” centers, including the Houry Center, Alaya prison, and a new center called Orkesh, five sources said.

In January, ISIS fighters attacked al-Sina’a Prison in the Ghweran neighborhood of al-Hasakah city in an effort to free about 4,000 men and boys detained for alleged ISIS links, sparking a 10-day battle with the SDF, backed by US airstrikes and US and UK troops. The SDF said that more than 500 ISIS attackers, detainees, guards, and their own forces died before they recaptured the prison but did not say how many of the dead were detainees. Detainees inside the prison during the battle told Human Rights Watch that several children were among those wounded and killed.

Citing security concerns, northeast Syrian authorities declined repeated Human Rights Watch requests to inspect prison cells holding foreign men, women, and boys.

Human Rights Watch is using pseudonyms and withholding other identifying details of most detainees, who said they feared reprisals by pro-ISIS detainees or camp authorities.

Violence and Death in Camps

During two visits to Roj and one to al-Hol in May, detainees begged for help, saying they were living under the constant threat of violence and death. At al-Hol, mangers only allowed Human Rights Watch to enter two small areas, saying armed ISIS members controlled entire sections of the camp.

Human Rights Watch separately interviewed 10 detained Iraqis and Syrians at al-Hol who said that ISIS members in the camp had killed their relatives, or robbed, threatened, or harmed them, accusing them of cooperating with camp authorities.

One man showed Human Rights Watch a wound on his chest that he said was from pro-ISIS detainees who shot him because they considered him an informant. A woman who had worked at a kindergarten camp said two ISIS members robbed her, pointed a gun at her, and warned her: “This is the last day you work at the kindergarten, or we will kill you.” She immediately quit.

The 42 people killed in al-Hol from January to mid-November included 22 women and 4 children, and 83 people were killed in the camp in 2021, the UN Human Rights Office said. From 2019 to 2021, at least 972 detainees in al-Hol, many of them children, were reported to have been killed or died from other causes, including accidents, malnutrition, and hypothermia, according to the World Health Organization and Kurdish Red Crescent.

In May, an 8-year-old Iraqi boy drowned in one of the many open sewage canals crisscrossing al-Hol, camp managers said. Days later, Human Rights Watch saw children playing in a camp sewage canal. The bullet-riddled body of an Iraqi woman was also found that month in an al-Hol sewage pit, camp managers said. In November, two Egyptian sisters, both under 15, were found dead in an al-Hol sewage canal after being raped and stabbed.

Aid workers have also been threatened, robbed, or even killed, in some cases forcing them to suspend operations, sources including two aid organizations operating in the region said.

In September, the SDF, aided by US military intelligence, carried out a three-week sweep of al-Hol, arresting 300 alleged ISIS operatives, confiscating explosives and hand grenades, and freeing six women who were found chained and tortured, including a Yezidi woman whom the US military said ISIS captured in 2014 at age 9.

No murders have been reported in Roj but more than a dozen women there said that pro-ISIS women had threatened or targeted them and their children. “They throw rocks at me and my son, saying I need to wear the veil,” a French woman said.

Camp managers at Roj and al-Hol, aid workers, and women held at Roj said that detainees, both children and adults, at times sexually abused other detainees, including children. Some women resort to sex work to buy food and medicine for their children, risking execution by ISIS enforcers for doing so, and children often work or beg for food, making them vulnerable to exploitation, aid workers said.

Among other case, an aid worker said, two pregnant women held in the camps alleged they had been raped in 2022 by masked men they believed to be camp guards. and a man held in the camp had raped a young boy.

“When we were under the Islamic State, we had to find a safe place to protect our children from the bombs, one Canadian mother in Roj said. “Now we have to find them a safe place to protect them from other people in the camps.” Like many women, the mother said she also needed to protect her children from increasing traumatization as the years passed by in the camps. Days earlier, she said, her young son had tried to hang himself with a tent rope.

Inadequate Medical Care

In both camps, detained women said shortages of medicine and medical care were severe. Many mothers in Roj said their children suffered from severe asthma exacerbated by fumes from an adjacent oil field but that they could not obtain sufficient oxygen or other medicine. Three women said that their children required surgery that they would have to pay for themselves, but they had no way to earn money inside the camp.

Women held in both camps said that guards delayed or denied requests to bring women or severely ill or injured children to hospitals for emergency care, and that some had died. A Doctors Without Borders report on al-Hol in September described camp authorities waiting so long to transport two young children needing emergency care to hospitals – two days in one case and hours in another – that both died en route, without their mothers.

Amira, a 32-year-old Egyptian widow held in Roj with her two young children, said she wanted to return to Egypt, a country with a record of mass abuses of terrorism suspects, if her children could receive medical care and start new lives there:

I have two kids, all of the time they are crying. They are asking, “Why we are in here?” My son is sick. He has a problem breathing. At night he goes, “hnghhh, hnghhh.” He needs surgery or something to help him breathe. [I say] “It’s okay, it’s okay, you will be fine… tomorrow we will go out.… And tomorrow comes and we do not leave. … Please, anyone [who] see this message, anyone responsible… please move. For the children, for kids. To get their rights.

Sources including aid groups estimated that hundreds of detained boys and men transferred from al-Sina’a to Panorama prison after ISIS’s attempted prison break in January have tuberculosis that was untreated for months, and that dozens need specialized surgery or advanced treatment for wounds or other medical conditions.

Food and Water Shortages

Food and clean water shortages, particularly in al-Hol, are recurrent. For two months over the summer, al-Hol detainees did not receive their basic food rations, an aid worker told Human Rights Watch. For several days during that period, authorities in al-Hol prevented all detainees in the “Annex,” the sections holding non-Iraqi foreigners, from going to the camp market to buy fresh food, milk, and bottled water, two detainees said. The authorities cut off the market access after a group of women complained of mistreatment by guards and interrogators, the two detainees said.

In Roj, one woman said that guards had entered a section of the camp in June and threatened to “take all boys ages 7 and up” if a woman did not return food she had stolen from the market.

Al-Hol also suffered water shortages after camp managers suspected that ISIS was smuggling arms into the camp with water deliveries, aid workers said.

Transfers of Women and Children to Other Detention Centers

Seven women in Roj described being detained in late 2021 and early 2022 by camp guards, two of them after several detainees staged a protest. Guards held about 20 women for periods between a few days and four months, leaving about 45 children behind, according to three women. One French mother with young children said that she was held for four months, first in a toilet stall, then in a prison:

They closed us into toilet stalls and interrogated us. I was there for two days, other women for many more. They told us, “You will never get out. You will never see your children. These days will be your last.” Please let me come home with my children, even if I have to go to prison. For the sake of my children. We have no rights here.

Women whom regional authorities allege are ISIS morality police are periodically transferred from the camps to a prison in al-Hasakah. Since October 2021, up to 55 of the women’s children have spent nights with them in prison and eight hours a day in a heavily guarded day care center inside the prison compound called Helat. The children are 18 months to 13 years old, Helat director Parwin Hussein al-Ali told Human Rights Watch in May.

Helat has Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck painted on its high walls, trailers that al-Ali said were donated by the US military that the children use for naps, movies, and other activities, and a swimming pool and flush toilets, though neither had water on the day that Human Rights Watch visited. Children from countries including France, Russia, Tajikistan and the UK played in a courtyard. Al-Ali said the center lacked funds for fresh food and toys.

Several of the 10 children Human Rights Watch spoke with there said they would rather live in the locked camps than spend nights in prison.

“Why are we in prison?” asked an 11-year-old boy from Tajikistan, who had a scar on his skull that he said was from an airstrike. “When will we get out?”

“In prison we just sit and do nothing and nothing and nothing,” said a 12-year-old girl from Azerbaijan.

During the January attack on nearby al-Sina’a prison, two ISIS suicide bombers tried to scale the walls of Helat but were killed by guards, al-Ali said.

Boys Detained Apart from Their Families

Scores or possibly hundreds of boys have been forcibly removed from al-Hol and Roj camps by Asayish and SDF forces and held in separate detention centers when they reach or approach adolescence, said mothers, boys who were taken, and several camp and aid workers. The UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria reported in September that those taken included “scores of boys ages 10 to 12” from al-Hol camp. A Doctors Without Borders report in November called the practice “routine and systematic.”

In many cases, guards took the children without informing their mothers and camp authorities did not respond to mothers’ pleas to know where their sons were held for weeks or months, mothers said, which would make their removals enforced disappearances.

Northeast Syrian authorities acknowledged that boys were taken but declined to say how many or where all of them were held. They said that nearly 110 boys are held at the Houry Center, a locked building with a courtyard that the Autonomous Administration calls a recreation center, and that older boys are then transferred to military prisons for men. Those prisons also hold boys who were immediately separated from their parents by the SDF upon their capture in 2019 or earlier. Several aid and camp workers and organizations said that they do not know all the places where the boys are taken.

Bawarmand Rasho, a regional official overseeing al-Hol and Roj, said that the authorities only took boys they considered a security threat. He denied accusations that the authorities did not inform mothers of the transfers. “We don’t kidnap them,” he said. “We say, ‘We are taking your child to a rehabilitation center.’”

“Abar,” an Egyptian mother held in Roj burst into tears as she said her son, then 14, was among four boys who had been taken without warning eight months earlier. “Please, please, can you help me find him?” she begged. “I know nothing about him.” Camp officials later told the mother that her son was brought to Ghweran, the prison that ISIS attacked in January. For months, Abar thought her son might be among the dead.

In July, camp officials gave the mother a brief audio message and photo of her son in which he said he was fine but looked gaunt and wore winter clothes although it was summer, a family member told Human Rights Watch. As of December, 14 months after her son was taken, Abar had still not seen her son.

“Bader,” a boy at the Houry Center who said he was 15 and a US citizen, said that armed guards took him from al-Hol in December 2020, when he was at the camp market, “without my family even knowing.” He said his captors detained him for a month incommunicado in a latrine with 18 other boys and men, then took him to the Houry Center:

I went out shopping and they just picked me up from the middle of the store. We were four kids. They sent us to little jails, two rooms. It was a toilet [latrine]… They kept me there for one month. … We told them, “Why? We didn’t do anything.” And they said, “If you guys are bigger than 12 years old, 13 years old, you are not allowed to stay in the camp.” It was actually cold in that time, and they didn’t let us get our bags or anything, our clothes. And then they brought us here.

Bader said his father had brought him, his eight siblings, and his mother to Syria to live under ISIS in 2016, telling them they were going camping. He said the authorities have only allowed two visits, from one family member, since he was taken to the Houry Center.

During Human Rights Watch’s visit, boys from about two dozen countries including Algeria, France, Germany, Morocco, Trinidad, and Russia milled around the Houry Center courtyard or sat on cots in dormitories with vacant stares. An aid organization provides basic limited instruction in subjects such as English, Arabic, math, and music but the center lacks sufficient resources, said Khadija Mussa, the camp administrator.

Like other boys whom Human Rights Watch interviewed at the Houry Center, Bader said that most of the time he does nothing:

You know how in our age outside, in schools, how we’re supposed to be like, eating, and walking around, and playing, and soccer, and bicycle, and learning, and stuff like that. It’s not only me it’s a lot of kids.… No one wants to stay, growing up here, doing nothing.

At least 60 other foreign boys and young men are held at Alaya military prison, two sources said. The foreigners are in separate cells from the other 800 detainees, most of them Syrians convicted of terrorism. When Human Rights Watch visited Alaya in May, 30 foreign boys and young men were held there. The number swelled during the security sweep in al-Hol, the two sources said.

The youths are held separately from the men in a “rehabilitation center,” the prison manager, Farhad Hassan, said in May. The boys come from more than a dozen countries including Afghanistan, France, Morocco, Pakistan, and Russia, he said.

Four youths interviewed said that all 30 boys and young men were confined for 23 hours a day to one crowded, locked cell with one shower and one toilet, with minimal activities. They said they spent the remaining hour in a courtyard that was too small for them to all play at once. For over a month, one boy said, they hadn’t had a football. The boys said they lacked adequate medical care and fresh food.

“Yasir,” a 19-year-old from France who said his parents brought him to Syria in 2014, said that armed guards took him from al-Hol camp in 2020, bringing him first to Houry and then to Alaya:

I was sitting in my tent and they came, the armed men. They said, “You’ll be coming back in two minutes.” But they never brought me back. Psychologically, I’m tired to death. I just want my mother. … I also need a doctor. I can’t move my left hand. My hand is dead.

Yasir’s left arm dangled limp by his side and a scar crisscrossed the back of his head – wounds he said were from a 2018 airstrike. Surgeons operated on his arm, but he needs special surgery that is not available in northeast Syria, a prison doctor said.

“Kemal,” a 20-year-old from Germany who was brought to Syria by his stepfather when he was 11, said armed guards snatched him from Roj in late 2019 in the middle of the night and brought him and three other boys to the Houry Center.

In May 2022, Kemal said, he was brought to Alaya. “Other boys get moved, too,” he said. “It’s scary to be here. Sometimes they [guards] come by surprise and we don’t know what’s going to happen.” Since being taken from Roj, he said, he had only seen his mother and three young siblings once, in 2020. “I can’t call my mother,” he said. “I hope she gets my letters.”

Some detained boys at Alaya and Houry said they sometimes did not receive family members’ letters for months. Delays were similar or longer in other prisons, family members said.

“Mum, more than a year has passed since the Red Cross came so I was surprised not to find a new letter,” Jack Letts, 27, a Canadian-British national until the UK government revoked his citizenship in 2019, wrote his mother in a September 2021 letter from a prison in northeast Syria. Letts’ mother, Sally Lane, received the letter seven months later.

Information from governments about detainees has also been scant or nil, several family members with relatives imprisoned in northeast Syria said. “It’s now four years that I’ve been asking you to clarify the state of my brother’s physical and mental health,” a Canadian woman wrote to Canadian authorities about her brother, whom she said was “very sick” when she last visited him in a prison in northeast Syria in 2021. “Do you have a medical report on his health?”

In October 2022, Germany repatriated Kemal along with 11 German women and children. When Kemal arrived, the federal public prosecutor’s office immediately detained him, saying they suspect he fought with ISIS at age 14 and 15 and that after being taken from Roj he had beaten and threatened other boys to try to make them support ISIS.

Abdulkarim Omar, the northeast Syria official, said that the Autonomous Administration was seeking international funding for 15 or 16 rehabilitation centers for boys and potentially girls as they become adolescents. In 2021, Fionnuala Ní Aolaín, the UN special rapporteur on countering terrorism, denounced the boys’ detentions at Houry and in prisons as “the de facto culling, separation, and warehousing of adolescent boys from their mothers” in “an abhorrent process inconsistent with the rights of the child.”

International Legal Standards

Countries have a responsibility to take steps to protect their citizens when they face serious human rights violations, including loss of life and torture. This obligation can extend to nationals in foreign countries when reasonable action by their home governments can protect them from such harm. International human rights law also provides that everyone has the right to a nationality. Governments have an international legal obligation to provide access to nationality as soon as possible to all children born abroad to one of their nationals who would otherwise be stateless. Everyone has the right to adequate food, water, clothing, shelter, mental and physical health, and fair trials. All children have the right to education.

Detaining people in inhuman or degrading conditions such as those in the camps and prisons in northeast Syria is strictly prohibited under international human rights law and the laws of war. Enforced disappearances, which include the refusal by authorities to provide information on what became of a person they detained or where they were being held, are also strictly prohibited. If widespread or systematic, enforced disappearances are crimes against humanity.

The Autonomous Administration’s indefinite detention of foreigners without providing them with the opportunity to challenge the legality and necessity of their confinement is arbitrary and unlawful. The blanket detention of ISIS suspects’ family members amounts to collective punishment, a war crime.

Under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, children should only be detained as an exceptional measure of last resort. Criminal liability should only be sought for children transitioning to adulthood in rare circumstances. Children should not be separated from their parents absent independent evaluation that separation is in the best interests of the child. Children associated with armed groups should be considered first and foremost as victims.

In separate rulings in February and October, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child found that France and Finland violated the rights to life and to freedom from inhuman treatment of children they had not repatriated from northeast Syria. In September, the European Court of Human Rights found that France violated the rights of women and children seeking repatriation by failing to adequately and fairly examine their requests for repatriation.

UN Security Council resolutions, including Resolution 2396 of 2017, emphasize the importance of assisting women and children associated with groups like ISIS who may themselves be victims of terrorism, including through rehabilitation and reintegration.

Recommendations

Countries should repatriate or help bring home detainees, prioritizing the most vulnerable including children and their mothers. UN entities, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and UNICEF, as well as the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS and donor countries, should work to safely resettle abroad foreigners facing risks of death or torture and other ill-treatment at home. Governments should provide those repatriated or resettled with rehabilitation and reintegration services and prosecute adults when warranted.

In the meantime, these countries, donors, UN entities, and the Coalition to Defeat ISIS should immediately increase aid to end inhuman and other degrading treatment through efforts that include improving food, shelter, medical services, and education for children. They should maintain family unity when in the best interests of the child and help local authorities remove boys and young men from military detention. They should increase communication between detainees and family members in northeast Syria and in countries of origin, including proof of life.

These governments and entities should also promptly resume stalled efforts to create a judicial process in northeast Syria or elsewhere to allow all foreigners to fairly contest their detention, allowing the immediate and voluntary release with safe passage of all those who will not be criminally charged or do not pose an imminent security threat.

Northeast Syrian authorities, including the Autonomous Administration, the SDF, and the Asayish, should cooperate with these efforts, allow aid groups and independent observers unfettered access to all detention sites, and ensure prompt treatment for detainees needing advanced and life-saving medical care.

Source: hrw