Personalities of Islamic State’s international brigade paraded before French court

The parade of personalities continues at the special criminal court in Paris, with four more suspects . . . Adel Haddad, Mohammed Amrii, Muhammed Usman and Osama Krayem . . . describing their family and personal backgrounds in Algeria, Belgium, Pakistan and Sweden. For the moment, the court is ignoring the crimes alleged against each man, and especially any question of religious motivation. That will come later.

One moment from Thursday’s hearing might be used to illustrate what has been going on at the special criminal court in Paris this week.

Just before the afternoon break, after two hours of questions about the childhood, schooldays and drug problems of his client Mohammed Amri, the defence lawyer Xavier Nogueras started talking about music.

The tone was the strangely intimate one which we have heard several times already between client and legal representative. It’s a face-to-face affair, ignoring the court and 500 spectators. Both are clearly playing a well-rehearsed scenario. Both know their lines.

“We have a tiny window of opportunity here,” the lawyer explained to Mohammed Amri, like a magician promising to produce a rabbit from inside his empty top hat. “This is our chance to talk about your personality. Afterwards, we’ll be reduced to facts, and that will be a lot harder.”

In the wake of the five harrowing weeks of testimony from survivors and the bereaved which have just come to an end, this is a chance for the defence teams to claw back some credit for the men they represent. Obviously, once the charges against each man and “the question of religion” are directly considered early next year, things will, indeed, become a lot harder.

So Amri told the court that he liked the French rapper Jul, someone called Lacrim, and . . . Kamikaz.

Nogueras sat down in the wave of laughter that followed that last observation. He had his rabbit by the ears. Mission accomplished.

The personalities of the suspects are among the few areas in which they can attempt to rejoin the human community from which the awful results of the crimes of which they are suspected have excluded them.

So, we have heard touching tales of happy childhoods, solid, supportive families, normality.

One suspect drove an ambulance for the Belgian social services, distributing food and blankets to the homeless. Another sent money to help orphaned children in Gaza.

The Berber-speaking Algerian Adel Haddadi testified in French.

Even Salah Abdeslam, the sole survivor of the November 2015 terror squads, has seen fit drop the rhetoric of avenging jihad and aim for a tone of conciliation and cooperation.

Haddadi and Amri have both expressed their sympathies for the suffering of the survivors and their families.

The court is being subjected to a charm offensive.

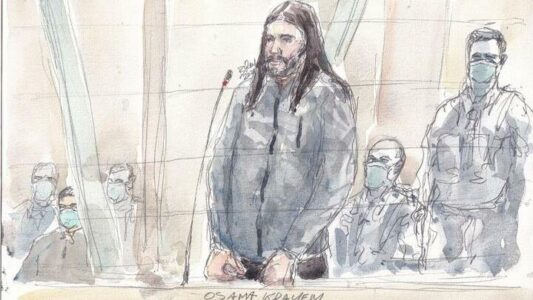

Osama Krayem is different. He is Swedish, with Syrian and Palestinian parents. His long hair makes him stand out from his shaven-headed co-accused. He keeps his answers short, refuses to go into details, even when encouraged by his legal team.

He told the court that his heart had been “hardened by the war in Syria”, birthplace of Krayem’s father.

Investigators suspect that he was one of the leading Islamic State organisers in Europe at the time of his arrest. Evidence links him to the Paris killers, and also to the 2016 Brussels’ attacks, in which 32 people died.

Thursday’s hearing opened with a statement from the tribunal president, Jean-Louis Périès, to the effect that a decision on the status of some of those who have applied to be recognised as civil witnesses will be made at the end of this trial, early next summer.

“The decision is too important to be made prematurely,” the president explained.

The practical impact of that final decision is anything but anodyne. I spoke to a man who left his then 15-year-old daughter in their second floor apartment overlooking one of the bar terraces attacked by the terrorists. He went down to help the injured.

The daughter panicked. Her father has since spent €13,000 on psychological treatment for the young woman.

“I want nothing for myself,” he explained, “but I would like help with the medical bills.”

The state, which will ultimately have to compensate those the court recognises as indirect victims, is anxious to limit the definition of “victim” as tightly as possible.

The trial continues.

Source: RFI