Pakistan battles rising terror threat in Afghan border regions

For the past two years, Pakistani labourer Nadir Gul has been unable to return to his native Kurram district, on the country’s northern border. The region, just 100km from Kabul, has been riven by terrorist violence since the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan.

“Close family members have died and I couldn’t go home for their funerals,” said Gul, a father of six, who lives with his family in a one-room shack in Islamabad. “For us, there is no joy left any more. It’s all just misery caused by the fear of attacks by the Taliban.”

More than 1,500 people were killed in terrorist attacks in Pakistan last year, according to the South Asia Terrorism Portal, a private monitor. That is more than 50 per cent up on 2021’s toll and thrice the number in 2020, the last full year before US forces withdrew and the Taliban swept back to power in Afghanistan.

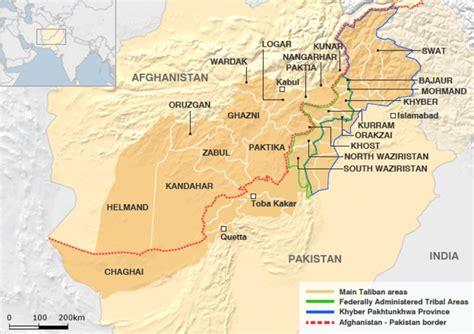

The surge in violence has brought about officials’ fears of Pakistani Taliban militants based in Afghanistan carrying out attacks next door. The group, which has historic links to the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaeda but has operated independently, formed in 2007 out of militant networks in the border region in opposition to the Pakistani military and government.

“In 2021, we were confident that the Taliban in Kabul will defend Pakistan’s interests and prevent terrorist attacks in Pakistan. Today, that is not the case,” said a senior Pakistani security official.

The person added that at least 2,500 people had been killed in attacks linked to militants based in Afghanistan since the Taliban returned to power in Kabul in August 2021.

For years, Pakistan drew a distinction between the Taliban in Afghanistan — which was considered more co-operative towards Islamabad — and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, as the Pakistani Taliban is formally known.

The latter group, which has been designated a terrorist organisation by the US and UK, has launched dozens of terror attacks, including a 2014 assault on a school in Peshawar that killed 149 people and the attempted assassination of education campaigner Malala Yousafzai in 2012. One Pakistani official called the Pakistani Taliban “the largest threat to our country”.

Pakistan had hoped that the Afghan Taliban would help rein in other militants after the country supported the Islamist group during the two-decade US occupation of Afghanistan, despite Islamabad being aligned with Washington on other security priorities in the region.

Islamabad has facilitated travel for top Afghan Taliban officials to Qatar, where the group’s political office is located, for negotiations with the US, and western diplomats have in the past claimed that top Afghan Taliban members were allowed relatively unfettered travel in Pakistan.

Senior Pakistani security officials told the Financial Times that keeping “lines of communications” open with the Taliban was important to maintaining leverage with the hardline group. But the limits of that strategy have now come into question.

“The Afghan Taliban had promised not to let their soil be used against Pakistan,” said Farooq Hameed Khan, a security commentator and retired army commander. “But that promise has been broken.”

According to the Islamabad-based Pakistan Institute for Conflict and Security Studies, the number of terrorist attacks in Pakistan jumped 79 per cent in for the first six months of 2023, compared to the same period in 2022.

“The Pakistani Taliban based inside Afghanistan have become an extension of the Afghan Taliban,” Khan added.

He warned that Pakistan’s deteriorating security situation could force Islamabad to block trade routes to landlocked Afghanistan or launch aerial attacks on Pakistani Taliban bases over the border.

But western diplomats in Islamabad said that reprisals by Pakistan’s military could further destabilise the country as it prepares for parliamentary elections expected in February.

Last week, Pakistan exchanged unprecedented attacks with neighbouring Iran. Both Islamabad and Tehran said their attacks were targeted at separatist terror groups in border provinces.

Islamabad late last year began expelling tens of thousands of the approximately 1.7mn unregistered Afghan refugees in the country, with officials citing the rise in terror attacks and alleging militants were slipping over the border.

“As Pakistan goes in to election [campaign], the risk of [terrorist] attacks will grow,” said one western diplomat in Islamabad, who cited the assassination of former prime minister Benazir Bhutto on the campaign trail in 2007, which Pakistani and US authorities blamed on the Pakistani Taliban.

Analysts said that such a military crackdown would not stamp out terrorism in urban areas, however. Pakistan’s police forces have struggled to maintain law and order, with senior officers complaining of swift and frequent transfers of people in leadership positions, which have eroded the forces’ capacity.

“You must build up the police as the first responder to terrorist threats,” said Kaleem Imam, a former police chief. “The police today need more resources and security of tenure.”

The country’s fragile economy is also slowly climbing out of a crisis, having narrowly avoided a default last year by securing a $3bn IMF rescue programme that has forced a caretaker government to implement painful reforms including cutting energy subsidies and improving tax enforcement.

Imam also called for Pakistan’s intelligence services to be more closely incorporated into efforts to combat terrorism.

“Dealing with the terrorist threat is not just about confronting them on the borders,” he said. “It’s also about securing Pakistan internally.”

Source » ft.com