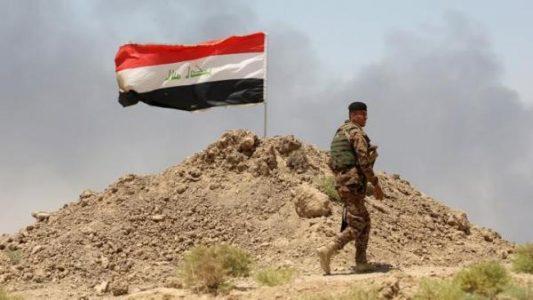

ISIS Never Went Away in Iraq

On August 31, 2010, President Barack Obama declared an end to the U.S. combat mission in Iraq, turning the page on American military involvement in the country that began with the invasion in 2003 that toppled Saddam Hussein from power. Eight years later, attacks this week in Anbar Province and Kirkuk, attributed to ISIS, show just how difficult it is to stabilize a country that has seen little stability since then—and not for want of trying.

ISIS is supposed to have gone away. Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi declared “final victory” over the group last December after his troops, allied with Kurdish fighters and Shia militia, and supported by U.S. air strikes and military advisers, pushed the insurgents out of Iraq’s cities. At the peak of their powers in 2014, ISIS had controlled a vast swath of territory across the Iraq-Syria border. U.S. military officials say ISIS has now been driven out of 98 percent of the territory it once controlled. But the group has reappeared in central Iraq, carrying out attacks that The Washington Post described as “chillingly reminiscent of the kind of tactics that characterized the … insurgency in the years before 2014.” All this despite the billions the U.S. and its allies have spent to bolster Iraq’s security, its civic institutions, and its infrastructure.

This week’s suicide attack in al-Qaim, a district in Anbar Province that is near the border with Syria, killed at least eight people. Separately, a suicide bombing in Kirkuk killed two police officers. ISIS is active in both areas.

“ISIS never went anywhere. It’s still on ISIS 1.0,” Michael Knights, an expert on Iraq at the Washington Institute, told me. “All they did was in every area where they lost the ability to control terrain, they immediately transitioned to an insurgency.”

The Iraqi government and its allies, rightly, viewed the victories against the group last year as a moment to celebrate for a country coming off years of unrest. But ISIS, Knights said, merely viewed the loss of the major Iraqi cities it had controlled as a milestone on a continuum of conflict. “They don’t view it as the end of their operations,” he said. “They just view it as a movement to a new phase of their operation.” Knights recently visited Baghdad and met with officials there.

Indeed, in the three predominantly Sunni provinces where ISIS was once dominant—Diyala, Salah ah-Din, and Anbar—the group has now returned to conducting potent insurgent attacks. “The quantitative figures say that ISIS is operating at an early 2013 level in most places,” Knights said. “But qualitatively, more important, you can see that ISIS had returned to the very targeted violence that allowed it to dominate the rural areas in 2012-2013.”

Knights, who studies the insurgency in Iraq closely, says one good indicator of whether ISIS is regaining strength in Iraq is to see how many moqtars—village elders—are being killed by the militants. Over the past six months, he said, an average of three and a half moqtars have been murdered by ISIS each week.

“Now, that means in a month, 14 villages see the most important person in the village murdered by ISIS. Over a six-month period, that means that 84 villages have seen the most important person in their village murdered by ISIS,” he told me. “And over a year, that means 168 villages have seen the most important person in their village murdered by ISIS without the security forces being able to do anything about this.” Extrapolate that to the year 2020, and that figure will be 500 villages—just at the current rate, he said.

“What this does is completely erode the faith of the population in the security forces,” he said. “They don’t cooperate with the security forces out of fear. They don’t oppose ISIS. They don’t inform on ISIS. And, eventually, their kids start to see ISIS as the strongest force in the area.”

What ISIS did last year was to disperse and melt in among the civilian population. Fighters hide in the sorts of places where it is the hardest to find them: caves, mountains, river deltas. ISIS has also returned to the playbook that made it a force in 2012 and 2013: attacks, assassinations, and intimidation—especially at night.

“You can say that almost all of Iraq has been liberated from ISIS during the day, but you can’t say that at night,” Knights said. “At night, ISIS controls a lot more territory than it does during the day. If you speak to Iraqi and coalition intelligence officials in Baghdad … they’ll tell you that Islamic State fighters have complete freedom of maneuver at night in many areas.”

This presents a challenge for Iraq, which is still trying to cobble together a government after recent parliamentary elections. The difficulty of government formation, protests against corruption, meddling neighbors, and sectarian tensions are all putting a strain on the fragile democracy. If ISIS stays at its present strength for the foreseeable future, the government will find it virtually impossible to stabilize the Sunni areas, an essential step if Iraq is to survive in its present form.

Part of the challenge facing the Iraqi security forces is transforming themselves from a force that fought and reclaimed territory from ISIS in the cities to one that can carry out a massive and effective counterinsurgency in rural Iraq. Its forces need to be able to provide credible assurances to tribal leaders, often from a different sect, tribe, and part of the country, that informing on the local ISIS cell is not only the right thing to do, but also won’t get them killed because they’ll be protected by Iraqi forces. This takes years—not to mention money. In many ways, what ISIS is doing is far easier.

“The ISIS guy, his job is to sit in his cave, and [say] one night this week, ‘Let’s go into that village and shoot that moqtar in the head,’” Knights said. “Who’s got the easier job?”

Estimates of just how many ISIS fighters remain vary wildly. The UN last month estimated that there were between 20,000 and 30,000 ISIS fighters in Syria and Iraq, evenly divided between the two countries. In a report to Congress, the U.S. Defense Department’s own inspector general put the number of ISIS fighters in Iraq at between 15,500 and 17,100 (with an additional 14,000 in Syria). Those figures resemble the assessment of ISIS’s strength at the height of the insurgency in 2014.

Speaking to reporters this week, General Joseph Dunford, who is the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, dismissed those assessments, saying he had “confidence in some statistics and not in other statistics.”

“I don’t have high confidence in those particular numbers,” he said, adding: “We know there are remaining residual pockets of ISIS inside of Iraq, which is why we’re working with Iraqi security forces. We’ve acknowledged that remaining work has to be done, but I certainly would not say that ISIS has the same strength that it had at its peak.”

Knights called the estimate of approximately 15,000 fighters “completely made up.” “How do you classify an ISIS guy?” he asked me. “Is he the foreign fighter? Is he the leadership cadre? Is he a guy who’s been in ISIS and has killed some people, but he might leave the movement if it’s getting weak? He just wants to be a bully, a gang leader—and he’d be just as happy doing that in a government militia.”

Knights said there might be 15,000 people who work in some capacity in partnership with ISIS, but there will be a far lower number of actual fighters. There are several reasons for this: ISIS has been pummeled in Syria. The Iraqi security forces are better led and supported than they used to be. Iraqi Sunnis who lived under ISIS rule know firsthand the cruelty the group is capable of. ISIS simply does not have the capability, nor the support, to take over Iraq’s cities and its oil fields as it did in 2014.

“The problem they pose is not that they can take over cities. It’s not that they can stop Iraq from exporting oil. It’s not that they can assassinate the prime minister,” Knights said. “The problem with ISIS is that they will make it impossible stabilize the center, north, and west of the country. They’re like poison in the ground, or salt in the earth. Until they are gone, you can’t rebuild anything. You can’t make the economy work again. You can’t get people to move back to their villages, come out of their displaced-persons camp. You just can’t normalize life while they’re out there.”

Source: theatlantic