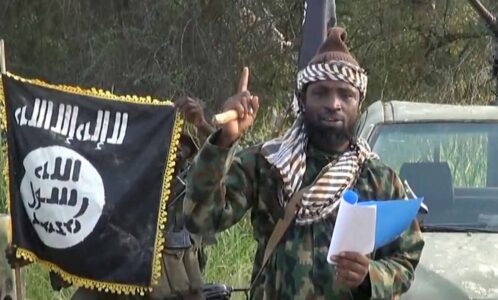

Islamic State assassination on Boko Haram leader Shekau – warning shot to global security

The assassination of Boko Haram’s leader on the direct orders of the new head of Isis spells trouble for northern Africa, Afghanistan – and consequently, global security at large.

Abubakar Shekau, leader of the extreme Islamist movement Boko Haram in northeastern Nigeria, died last month after detonating an explosive device while being pursued by the rival extremist faction, ISWAP (Islamic State West Africa Province). Earlier this week, ISWAP confirmed it had carried out the killing on the orders of the new head of Isis, Abu-Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qyurashi, who is presumed to be operating from Iraq.

It appears the motive is part of a plan to strengthen Isis influence in Boko Haram, which is itself a loose part of the wider Islamist movement that is gaining increasing influence across the Sahel region of northern Africa – and in turn, strengthening the international capacities of Isis to a worrying degree.

The killing of such an infamous Islamist leader has come at a time of increasing insecurity across the Sahel, which includes the northern part of Nigeria. And security throughout Nigeria is proving especially problematic. Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari won an election in 2015 on a platform to increase internal security, but has concretely failed to do so.

On 30 May, 136 schoolchildren were abducted by armed gunmen – bringing the total number of student kidnappings to more than 800 in the past six months. The kidnappings are mainly down to Islamist militias in the north, but Nigeria is also facing separatist militias in the southeast and southwest.

In spite of this, Buhari remains popular – his All Progressives Congress Party controls the parliament and most state governorships, and he is expected to be re-elected next year, so there is little prospect of changes in the security posture. This is as much bad news for Nigerian civilians as it is good news for Islamist militias, especially as their influence is growing in states to the north.

Multiple militias are involved across five countries in the Sahel – Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Chad – and many are loosely connected to al-Qaida or Isis. Isis is intent on extending its influence also throughout East and Central Africa, including the DRC and northern Mozambique. In the Sahel, the main focus is on the tri-border area of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, where the main Western military involvement has come from France’s Operation Barkhane counter-insurgency force. The US army and the CIA are also involved, as are British special forces, and the UN maintains a substantial stabilisation mission in Mali.

However, France’s role as the major operator has not been without substantial cost. As Le Monde Diplomatique put it earlier this year, the military operations, “…may be giving France an aura of European leadership in security, especially in conflicts to its south. But the costs are exploding: nearly €1bn annually; 17,000 soldiers on rotation each year (a quarter of the army’s combat troops); 55 killed and 300 wounded to date; and, politically, the taint of neo-colonialism.”

The conflict continues, with no end in sight, and even the deployment of a further 550 French troops earlier this year has had little effect. A sense is growing in France, as well as among its allies, that this war is unwinnable – and this sentiment is intensifying with the retreat of Western forces from Afghanistan.

Source: Open Democracy