Iraq Could Be the Next Arena for Turkey and Iran’s Rivalry

Iraq could become a new flashpoint of tensions between Turkey and Iran, as shifting geopolitical dynamics continue to reshape the Middle East. Over the past year, Israel’s military successes against Hamas and Hezbollah, combined with the fall of the Assad regime in Syria, have weakened Iran’s regional influence, prompting Tehran to reconsider its strategic objectives. At the same time, Turkey has recently seen its regional position improved due to its ties with the new authorities in Syria, even as it continues to pursue military operations in the northeast against Kurdish militias with ties to the PKK, a Kurdish insurgency based in Iraq’s Kurdistan Region. As a result, Iraq’s political landscape has become a critical arena for both powers to assert their influence.

For years, Iran’s overland logistical and military supply routes to Lebanon via Iraq and Syria enabled it to support a regional network of proxy factions. But since the overthrow of former Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad regime in December 2024 and Israel’s weakening of Hezbollah since July 2024, Iran now finds itself on the back foot, increasing the strategic importance of its longstanding influence in Iraq.

By contrast, Turkey finds itself with momentum on its side, having made bold, assertive foreign policy moves with tangible successes. While much of the focus has been on Ankara’s strengthened ties with Syria’s new rulers, Turkey has also notched further diplomatic wins in Iraq. On Jan. 26, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan visited Baghdad, extending Ankara’s push for unity within the Iraqi government, particularly in relation to the Kurdish Region of Iraq, or KRI. For Ankara, the potential for divisions both in Baghdad and between Baghdad and the KRI hamper the stability needed to promote Turkey’s economic inroads in Iraq, but also to marginalize the PKK.

Throughout 2024, Turkey made other key moves in Iraq. That included penning an important memorandum of understanding with Baghdad in August 2024 that pledged deeper cooperation on defense and security. That agreement also saw the establishment of a Joint Security Coordination Center in Baghdad for intelligence-sharing and counterterrorism purposes, as well as cooperation over Ankara’s military training facility in Bashiqa. Though the facility has housed Turkish forces since 2015, it was previously unauthorized by the Iraqi government, making it a point of tension with Baghdad until the recent agreement.

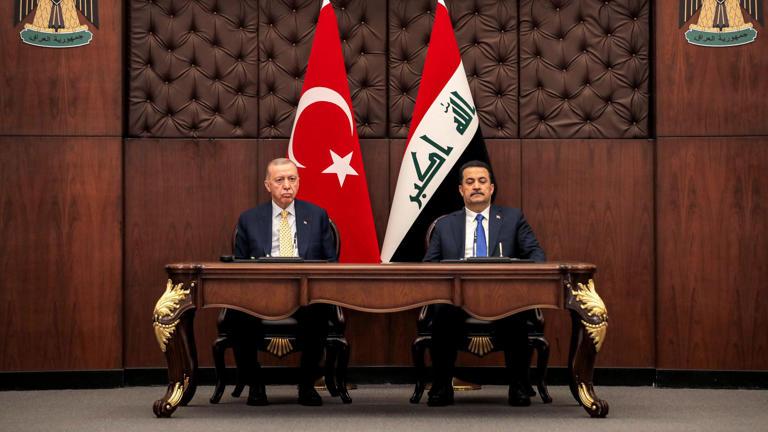

The August 2024 memorandum of understanding in turn built on past talks, including what was dubbed a “historic visit” in April by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to Baghdad, where he met his Iraqi counterpart, Abdul Latif Jamal Rashid. Following that visit, Ankara scored another diplomatic win, as Baghdad agreed to declare the PKK a banned organization that same month, enabling Iraqi security forces to prosecute and target members of the group.Ankara has long pushed Baghdad to take a stronger stance against the PKK and has intermittently launched unilateral operations targeting the PKK on Iraqi territory for years, so the agreement potentially removes another major irritant to bilateral relations.

Turkey’s diplomatic efforts now put it on a potential collision course with Iran, which has long used its support of various Shiite political factions to exercise considerable sway in Iraq.

It can also create a safer environment for Ankara’s economic ambitions, most notably demonstrated in the Development Road project, a $17 billion infrastructure initiative that would link Iraq’s Grand Faw Port in Basra to the Turkish border via a 1,200-kilometer rail and highway connection. The project is ambitious in logistical terms alone, but ensuring security within Iraq is a must for it to proceed at full scale.

This is where the dynamic between Turkey and Iran comes into play. Since the territorial defeat in 2017 of the Islamic State, in which Iran-backed Iraqi militias played a role, successive Iraqi governments have sought to reduce Baghdad’s dependency on external powers. However, Iran’s role in the country has remained substantial.

Turkey’s diplomatic efforts now put it on a potential collision course with Iran, which has long used its support of various Shiite political factions to exercise considerable sway in the country. Ankara’s military cooperation with Baghdad also jeopardizes the hegemony of the Iran-backed militias, which have strengthened their grip on the country since being formally incorporated as official Iraqi security entities.

The Development Road could pose a similar threat to Iranian interests in Iraq, as it could lead to a diversification of Baghdad’s economy. This is particularly significant considering Iraq’s previous economic dependency on Tehran, particularly with regard to the supply of gas, electricity and transportation.

More broadly, Iran is also bitter over Turkey’s gains in Syria after Assad’s downfall, with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei suggesting a “neighboring country” conspired to topple Assad, in what was seen as a thinly veiled reference to Turkey.

Given Iran’s setbacks in both Syria and Lebanon, Iraq has become even more critical for Tehran’s efforts to salvage its regional influence. Similarly, Turkey could see Tehran’s influence as a potential obstacle, particularly if Iranian militias try to obstruct or block parts of the Development Road, including by exerting pressure on the government in Baghdad. For now, Turkey has pursued a measured approach toward Iran, with Fidan expressing a desire for cooperation with Tehran concerning the PKK.

Still, the Kurdish regions may also become a flashpoint. In the KRI, Ankara has backed the KRI’s Kurdistan Democratic Party, or KDP, as a useful counterbalance against the PKK, while more broadly aiming to unify the KRI factions.

On the other hand, Tehran has long carried out attacks on the KDP, seeing it as a potential source of support and encouragement of Kurdish separatism within its own borders. Moreover, the KDP is the rival party of Iran’s traditional KRI partner, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, or PUK, which Tehran had leveraged against Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988 and continued to align with thereafter, seeing it as a counterbalance to the KDP.

Yet, the KDP’s victory in the latest KRI regional elections in October 2024, in which it won around 800,000 votes compared to roughly 400,000 for the PUK, has also boosted Turkey’s objectives in the KRI, while delivering a further setback to Iran.

Still, while Iran has at times cooperated with Ankara to address the PKK threat, Tehran’s past efforts to leverage Kurdish factions in not just Iraq, but also Syria, suggest the Kurdish regions could once again become a tool for Iranian influence.

As Hamidreza Azizi noted,during the final phase of Assad’s rule, Iranian-aligned forces strategically pulled back from key locations in eastern Syria, particularly Deir ez-Zor near the Iraqi border, allowing the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF-which Turkey is now fighting-to assume control.

That indicates Tehran may be laying the groundwork for future cooperation with the SDF, especially in light of increasing uncertainty regarding U.S. policy under the administration of President Donald Trump. Ultimately, the possibility of a tactical alliance between Iran and the Syrian Kurdish factions cannot be ruled out, should Tehran aim to salvage influence in post-Assad Syria.

As for the PKK, Ankara has in the past accused Tehran of backing the group, but Iran’s relations with the PKK have been more complex and pragmatic than that in recent years. That still might leave room for tacit Iranian tolerance of the group if Tehran sees it as a useful bulwark against Ankara.

Source » msn