In post-war Lebanon, Hezbollah grapples with new relationship to the state

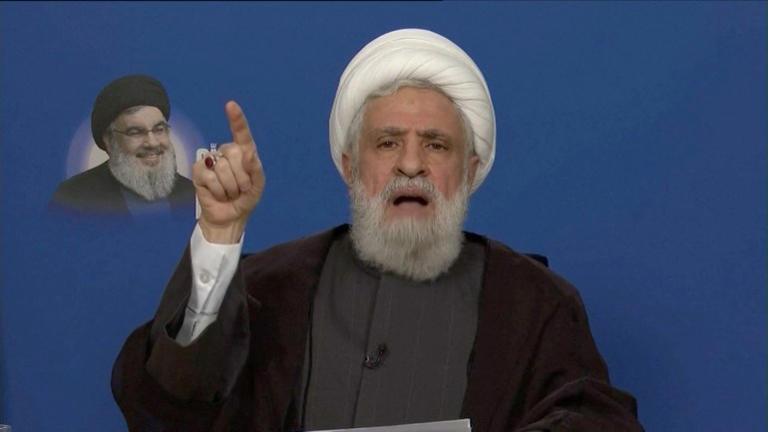

Hezbollah rallied thousands of its supporters for the funeral of its longtime leader Hassan Nasrallah, who was killed in an Israeli air strike in September.

The funeral on February 23 was an opportunity for the Lebanese group to send a message: Despite the losses it has experienced in the past several months, it is still strong and should not be underestimated.

But analysts told Al Jazeera the show of strength does not make up for the impact of Israel’s war against Hezbollah, which saw much of the group’s top leadership killed and a significant portion of its military arsenal reportedly destroyed.

When a ceasefire was finally announced on November 27, Hezbollah was left battered and exhausted.

The ceasefire stated that Hezbollah would retreat north of the Litani River and away from Lebanon’s border with Israel while Israeli forces would leave southern Lebanon and a newly empowered Lebanese military would control the south.

Days later, Hezbollah lost one of its most crucial allies, the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, which fell in a lightning opposition offensive.

It now finds itself at a crossroads.

Hezbollah weakened

“Hezbollah is in a difficult position,” Imad Salamey, a senior Middle East policy adviser and associate professor of political science and international affairs at Lebanese American University, told Al Jazeera, adding that the group is “facing its weakest moment in decades”.

Before September, Hezbollah was the most influential political actor in Lebanon and reportedly one of the world’s most heavily armed nonstate actors. It was formed to repel an Israeli invasion in the 1980s, held out against a major confrontation with Israel in 2006 and built its arsenal and manpower up since then.

It has often been described as a “state within a state” and also provides key services to its predominantly Shia Muslim supporters – a community historically overlooked and underserved by the Lebanese state.

A day after Hamas’s attacks on southern Israel and Israel’s launch of a genocidal war on Gaza in October 2023, Hezbollah entered the fray, engaging Israel along the border to pressure it to stop attacking Gaza. Its intervention was much anticipated, given that Hezbollah’s position has long been in support of Palestine and against Israel.

The conflict escalated in September when Hezbollah pagers and walkie-talkies exploded in attacks blamed on Israel. Israel also launched a day of air strikes across Lebanon on September 23 that killed at least 558 people, mostly civilians. The air attacks continued, and four days later, Nasrallah was killed. Many of Hezbollah’s military and religious leaders have also been killed since, including Nasrallah’s successor Hashem Safieddine in early October.

Israel destroyed infrastructure and homes across Lebanon, targeting parts of the country where Shia Muslims – Hezbollah’s support base – live, such as southern and eastern Lebanon and Beirut’s southern suburbs. It invaded Lebanon in October, particularly devastating the south, where it wiped out entire villages.

Hezbollah was left militarily weakened and unable to now fight back against Israel in the same way it used to.

“[New Hezbollah Secretary-General Naim] Qassem has inherited a weaker Hezbollah from his predecessor Nasrallah, and it will be interesting to see if he’d be as smart of a navigator given that so much of Nasrallah’s success was based on the party’s ability to project power,” Elia Ayoub, a Lebanese researcher and author of the Hauntologies newsletter, told Al Jazeera.

“Whether or not they decide to adopt a completely different methodology or not is what we’ll see in the coming months.”

A new political system and leveraging anger

The other sources of Hezbollah’s strength have been the support it receives from Iran, both material through Syria and financial, manifested in the social support systems it ran and in its political representation and influence.

However, as international attention increased on Lebanon after the ceasefire, its parliament was encouraged to select a new president and prime minister in early January, ending two years of government paralysis.

For the first time since 2008, Hezbollah and its sister Shia party, Amal, were not able to nominate every Shia granted a ministerial portfolio in the new cabinet.

“Hezbollah no longer has the financial means, open Iranian backing or clear military options to resist these changes,” Salamey said.

To make the best of the situation, Hezbollah has tried to leverage what it can, Karim Safieddine, a Lebanese political writer and doctoral student in sociology at Pittsburgh University, told Al Jazeera.

“Hezbollah’s goal today is multifold,” Safieddine said.

“[They want to] develop the resentment of the Shia community in the pursuit of consolidating control over it, find a way to navigate the fact that it’s facing extreme financial challenges – using international support to the government is one way but also while locating credit – [and] continue to justify holding arms in the name of state weakness and continued Israeli violations.”