How the FBI trapped Islamic State Beatle Aine Davis

Kamran Faridi was a generous benefactor, known in the circles in which he moved between Pakistan and Turkey for helping Palestinians, Syrians and orphans in need.

But Faridi’s gestures of largesse did not find favour with everyone he met.

Faridi spoke in an American accent that still betrayed its Pakistani origins. He drove a red Mercedes and wore a Rolex watch. And although sometimes concealed behind a baseball cap and shades, Faridi made little effort to hide his own affluent lifestyle.

One volunteer with Syrian aid charities who knew Faridi in Turkey told Middle East Eye: “He was always asking if there were any projects he could get involved in. He always wanted to pay for everything for everyone. I don’t like that style.”

A Pakistani-American dual national, Faridi had travelled into opposition-held Syria at the height of the country’s civil war. He talked of building an orphanage there through IHH, the Turkish humanitarian organisation.

He had contacts with charities based in Konya, a southern Turkish hub for Syrian aid. He had plans as well, he told acquaintances, to buy a religious school (madrassa) for Syrian children growing up as refugees in Turkey.

Faridi, who was also known to some in Turkish as Ebu Muhammet Amerika, appeared to be a successful businessman. He had established an import-export company in Turkey, trading in wholesale goods, with interests too in the Turkish tourism industry.

According to one person who met him, Faridi said he was also discreetly involved in trafficking artefacts.

“He said he was dealing stuff. He showed us statues, Buddha statues or something like that. That’s why he said he travelled, that was his line of business,” they said.

But there was more to Faridi’s itinerant lifestyle than met the eye.

In November 2015, Turkish investigators began digging into the Pakistani’s background after a luxury villa he had rented a few months earlier in Silivri, a seafront suburb west of Istanbul, was raided by counter-terrorism police acting on a tip off about a planned Islamic State attack on the city.

Six men were arrested, including Aine Davis, a British man alleged to have been a member of the IS execution cell dubbed “the Beatles” and a subject at the time of an Interpol red notice.

Later, it was revealed in court that US and British intelligence agencies told Turkish officials that Faridi was not linked to IS. Instead, it was claimed, he had ties with Jabhat al-Nusra, the Idlib-based hardline Syrian militant group then still aligned with al-Qaeda.

What Turkish officials do not appear to have known, nor been told by their western intelligence contacts, is that Kamran Faridi was himself working for another organisation: the FBI.

Faridi had not been among the six men arrested at the Silivri villa in that early morning raid on 12 November. Instead, he had left Istanbul for New York via Amsterdam a few days earlier.

In a months-long investigation, Middle East Eye has been able to piece together the labyrinthine events surrounding this Pakistani street criminal turned US federal agent, his effect on those who came into his orbit – and how he himself ended up in jail after falling out with his US intelligence bosses.

Alwalid Khalid Alagha needed a home. A large home.

A Palestinian then in his mid-2os, Alagha grew up in Pakistan before travelling to Turkey to claim refugee status along with his mother and his nine sisters.

It is unclear how Alagha and his family reached Turkey. He would later admit he had entered the country illegally but claimed to have travelled to Turkey directly from Pakistan. Prosecutors accused of him of having been in Syria.

Alagha also had two wives and four children. The family, including his mother and sisters, had been living in a property in Sirinevler in central Istanbul, but neighbours had complained to police about the noise.

Alagha’s refugee status meant he was unable to take out a tenancy agreement in his own name, never mind afford the cost of a property big enough to accommodate his extended family comfortably.

But he had connections. Alagha’s family was originally from Gaza but he had grown up in Pakistan because his father had travelled there in the 1980s to join the Arab Mujahideen fighting against the Soviet Union in neighbouring Afghanistan.

As well as a fighter, Abu al-Walid al-Filistini was a jihadist scholar of renown, once praised by al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri as “a man of the sword and the pen”.

In later police interviews and court testimony seen by MEE, Alagha said he had been introduced to Faridi by a mutual acquaintance in Pakistan as someone who could help him.

“Kamran Faridi was known as a benevolent person who helped orphans, Palestinians and Syrians,” said Alagha.

But sources spoken to by MEE suggest Faridi had cultivated Alagha because of the reputation his father enjoyed in militant Syrian opposition networks, which at the time were dominated by hardline Islamist factions including Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham.

One source said: “Faridi piggybacked off Walid’s [Alagha] name to get into the world. Your references need to be deep. Faridi bought his way in through Walid. He kept saying how great his father was.”

The men talked on the phone for eight or nine months, Alagha said.

Then he sent Faridi photos of a new property development that had caught his eye in Silivri: large luxurious villas, with swimming pools and private beaches. Ideal for big families.

According to Alagha, Faridi agreed to rent one of the properties on behalf of the family for 3,000 Turkish lira a month – then the equivalent of about $1,100. He travelled to Istanbul to finalise the paperwork in August 2015.

The relationship between the men deepened. Faridi included Alagha in some of his business dealings, sources said. The pair were seeking a shared office in Istanbul, and drove together to Konya in September 2015 to spend Eid al-Adha in the religiously conservative Turkish city.

Alagha spent just a day in Konya, a journey by car of about eight hours and 700kms from Istanbul. During court hearings he was quizzed about why he and Faridi had driven so far for such a short visit.

Faridi, Alagha said, had invited him to Konya to pray. He also had a beautiful car, he added – a Mercedes.

“Ebu Muhammet [Faridi] has a lot of money. Ebu Muhammet said he likes to travel a lot.”

But the relationship between the men could also be fractious.

One of MEE’s sources who knew both men said: “Walid and Faridi had digs at each other. Faridi said Walid could not be trusted. He would badmouth Walid. It didn’t make sense because he would badmouth Walid yet he was paying his rent.”

People who met Faridi said they had their own doubts at the time about whether he could be trusted, and suspicions about his motives and identity.

“He would just come and go. He would say one thing to someone and something else to someone else. He would say he knew a particular sheikh, and when we asked the sheikh if he knew this guy he would say, ‘What are you talking about?’

“A few times we caught him out on a lie, but we never confronted him. We just thought, ‘This guy is full of shit’, to be honest.”

Faridi’s connections were solid enough, however, for him to travel into a northwestern Syria dominated by Jabhat al-Nusra, where he moved around without seeming to attract suspicion.

Nusra had been established as a fighting force in Syria in 2011 with the approval of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the future self-declared IS caliph who at that time headed al-Qaeda’s operations in Iraq.

But by 2013 Baghdadi had split from al-Qaeda. And Nusra and IS were engaged in a fierce internecine conflict, competing for the loyalties of foreign fighters, weapons and territory at a cost of hundreds of lives.

Nusra remained loyal to al-Qaeda but also worked with, and fought alongside, other Syrian rebel groups against both pro-Syrian government forces and IS.

By 2015, when Faridi was in Idlib, Nusra was a key element within the Jaish al-Fatah (Army of Conquest), a rebel coalition that was then gaining territory in northwestern Syria.

The following year, Nusra split from al-Qaeda, renaming itself Jabhat Fatah al-Sham. It later became the main faction within Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the militant alliance which still controls most of Idlib.

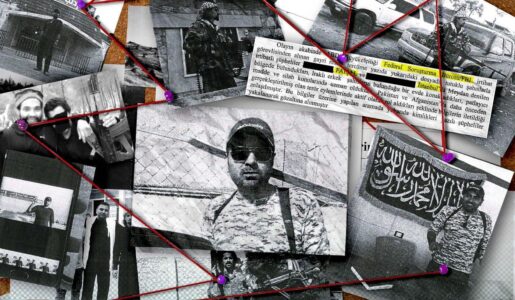

Photos from phones and laptops seized in the raid showed Faridi in opposition-held Syria in 2015. One showed him wearing a baseball cap, shades, and a holster with a handgun. In another he is standing in what appears to be an office in front of a shahada flag, which was commonly used as a banner by Jabhat al-Nusra and other Islamist militant groups.

A photo of a mobile phone screen shows him raising his finger at a road junction on the M4 highway outside the town of Saraqeb, a Nusra stronghold.

Material seized from phones also included images of Faridi’s Turkish residency permit and a Syrian ID card with his photo in the name of Mohammad Alomar and stating his place of birth as South Africa.

At his trial, Alagha also found himself under scrutiny over photos showing him posing with heavy weaponry. Other material found on his phones and laptop, including images showing cars with Aleppo number plates, indicated he had been in Syria, prosecutors said.

Alagha said the photos had been taken in the tribal areas of Pakistan, where gun ownership is common. He argued it was false to accuse him of links to IS because his loyalties lay elsewhere.

“They call us infidels,” he told the court. “They call Hamas infidels. They call Palestinians infidels. Why should I do evil to Turkey? No place other than Turkey accepts us.”

In early October 2015, Aine Davis sought the help of IS border commanders in Syria to cross into Turkey, according to an account of events leading up to the Silivri raid in Turkish court records.

A messaging app and phone number apparently being used by Davis was being monitored and he had been tracked electronically as he travelled across the country, reaching Istanbul on 7 November.

Phone records later produced in court indicated Davis was in contact with Alagha as he made his way across Turkey. At the same time, Alagha used a different phone number to keep in contact with Faridi.

Police then applied for a search warrant to raid the villa. Citing “reliable sources”, the warrant stated that Davis was a “known high-ranking operative of Daesh [IS]” who “may engage in organisational meetings and activities in our country, as well as engage in provocative and sensational actions”.

The warrant also sought authorisation to seize any knives or firearms found at the villa.

On the early hours of 12 November, Turkish counter-terrorism police raided the villa, arresting Davis, Alagha and four other men. In the days after the raid, Turkish officials said they had disrupted final preparations for an IS attack in Istanbul.

That scenario appeared all the more plausible after the IS attacks across Paris on 13 November, one day after the raid, when bombers and gunmen killed 130 people.

On the same day as the raid, IS also claimed responsibility for an attack in Beirut, in which 43 people were killed in two suicide bombings in the Lebanese capital’s southern suburbs.

The day of the raid saw another noteworthy event the targeted killing of Mohammed Emwazi in a US drone strike in Raqqa, the de facto capital of the Islamic State in Syria.

Emwazi, a British citizen, had gained notoriety in the British and US media as “Jihadi John”, the masked militant responsible for a series of beheadings of western hostages broadcast on IS media channels.

He was identified as the ringleader of a group called “the Beatles”, four Londoners alleged to have been leading figures in IS. Aine Davis had been named in the media as another member of the cell.

In court, Davis denied any association with IS, and denied knowing Emwazi in Syria. The pair had been linked in the media, he explained, because they had prayed at the same mosque in west London.

He had travelled to Istanbul, he explained, to acquire a fake passport because he had heard about an Interpol red notice for his arrest and did not want to return to the UK. The Interpol notice said material seized from the phone of Davis’s wife in the UK included photos of him with “guns, an Islamic flag, a dead martyr and other individuals who are also armed”.

Davis’s wife, Amal el-Wahabi, had been convicted of a terrorism offence in 2014 for trying to send her husband 20,000 euros in cash. Police had assessed the money was “destined to support the Jihadist cause in Syria”.

The red notice also said Davis had referred in messages to his wife to “being ‘on point’, believed to be a reference to assuming the most advanced position in a combat military formation advancing through hostile territory”.

But Davis denied being a fighter. He said he had travelled into Syria earlier in the war to undertake aid work, and had mostly been living in Gaziantep in Turkey since then.

He conceded he had acted “stupidly” by posing for photos with guns and armed militants – photos that would later pop up in British newspapers.

“Everyone was having photos taken with armed individuals like that in order to show off,” he told the court.

Questions about Kamran Faridi swirled over months of legal proceedings at the Istanbul court as prosecutors searched in vain for evidence to back up officials’ claims that the men arrested in the villa had been plotting a major attack.

Eventually, the prosecutors were forced to admit that no such evidence existed. The raid – and warnings of an imminent attack – had been based on information provided by an FBI liaison officer based in the US embassy, they said.

In a statement to the court in April 2016, prosecutors said some of those arrested in the raid on 12 November had apparent links with three other men who had been identified by the FBI as “experts in explosives and weapons”.

These three men had taken “an active role in terrorist acts that had taken place previously in Pakistan and Afghanistan”, and were linked to an earlier raid in Istanbul’s Meydan area in which explosives and firearms had been seized from a house occupied by a group of Iraqi men.

Intriguingly, one of these alleged explosives experts was identified as a man called Faisal, who had been in phone contact with Alagha. “Faisal” is Kamran Faridi’s middle name, although there is no evidence in the documents to confirm they are the same man.

Two other men, including a Pakistani man who Alagha said later was a childhood friend and a relation by marriage, were separately arrested by Turkish police but released without charge.

Prosecutors had concluded that there were no grounds to proceed against those arrested in the raid on the grounds that they had been preparing an attack.

“Sufficient evidence could not be obtained to file a public lawsuit against them that they committed a crime, other than the intelligence report of a foreign country, which does not have the quality of evidence,” prosecutors told the court.

But Davis, Alagha and the others arrested in the raid remained in prison.

Eventually, more than a year later, Davis, Alagha and Mohammad Ahmad Hamdan Alkhalaileh, a Jordanian man also arrested at the villa, were convicted on the lesser charge of membership of a terrorist group.

In May 2017, the three men were sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison.

It is not known what role Kamran Faridi played in bringing together the men arrested in the Silivri villa on the day of the raid.

Nor is it known whether he was the source of the intelligence provided by the FBI to Turkish police which prompted the operation.

According to legal papers seen by MEE, Faridi would later say he had been tasked with getting Davis out of IS-controlled Syria by a senior figure in Jabhat al-Nusra.

But the suspicion that western intelligence agencies had been involved in the case hung over the Istanbul court proceedings.

At one hearing, a lawyer for one of the defendants, frustrated at the continuing detention of her client long after prosecutors had conceded they lacked any evidence of an actual plot, suggested that the case had been tainted by “the misinformation of foreign intelligence units such as Mossad and the CIA”.

It remains unclear whether any local officials were aware Faridi was working for the FBI on Turkish soil at the time of the raid.

MEE has established that the FBI approached Turkish officials in February 2016 to propose that Faridi could work undercover for Turkish intelligence. But Turkish officials rejected the offer because, they said, Faridi’s cover had already been blown.

Faridi had in fact been working for the FBI for more than two decades, according to details of his career based on his own account first reported by Pakistan’s Geo News and verified by MEE.

Faridi, now 58, had grown up in Karachi. There, he had “started hustling” on the streets before making his way to Sweden and then migrating to the US in 1991, where he bought a petrol station in Atlanta, Georgia.

After contacting the FBI to complain of harassment by local police, Faridi was recruited to infiltrate a local Urdu-speaking gang, and then employed as a full-time informant in 1996.

In 2001, after the 9/11 al-Qaeda attacks in the US, Faridi joined the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force in New York.

He is said to have travelled the world infiltrating al-Qaeda networks in southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa and South America and disrupted suspected attack plots. Sources have told MEE he was also “loaned out” to other intelligence services.

But Faridi’s tenure as an FBI employee was abruptly terminated in February 2020 when he was dismissed following a disagreement with his bosses over an entrapment operation in which he had been involved targeting a Pakistani businessman, Jabir Motiwala.

The FBI accused Motiwala of being a senior member of D-Company, an organised crime gang based in India, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates with links to militant groups.

The alleged head of D-Company, Dawood Ibrahim, is subject to United Nations Security Council sanctions, which describe him as having “used his position as one of the most prominent criminals of the Indian underworld for most of the past two decades to support al-Qaeda and related groups”.

Motiwala, who was arrested in London in 2018 and faced extradition to the US on drug trafficking charges, maintained his innocence and said he was a victim of entrapment.

As part of the operation, FBI informants had arranged for four kilograms of heroin to be shipped from Karachi into the US, and laundered hundreds of thousands of dollars of drug trafficking profits.

Part-redacted US government legal papers describe the main FBI informant involved in the case as “a United States citizen, born in Pakistan, who has posed as a representative of La Cosa Nostra [the mafia] and Russian Organised Crime entities based in New York”.

After he was dismissed by the bureau, Faridi gave a statement to Motiwala’s lawyers in which he is understood to have said that his FBI bosses had told him to fabricate evidence against Motiwala.

He then flew to the UK in March 2020 with the intention of testifying on behalf of Motiwala, who was challenging his extradition in an appeal at the High Court.

But Faridi never made it to the courtroom. He was detained on arrival at Heathrow Airport on 2 March on a US arrest warrant, then flown straight back without facing extradition proceedings.

At Motiwala’s extradition hearing in London, his lawyers nonetheless put before the court Faridi’s statement. Lawyers for the US government immediately requested an adjournment.

Shortly afterwards, the US Department of Justice dropped charges against Motiwala and withdrew its extradition request. Motiwala was released and returned to Pakistan in April 2020.

In a statement, Motiwala’s London lawyers, ABV Solicitors, said: “It is strongly suspected that the decision was due to the admission to ABV Solicitors by an FBI informant Kamran Faridi, of being asked by the FBI to frame and fabricate evidence against Jabir Siddiq [Motiwala].”

ABV argued that the way in which Faridi had been prevented from giving evidence amounted to “an abuse of the court process as a form of prosecutorial misconduct.”

In November last year, Faridi was found guilty by a New York court of making threats against his former FBI bosses after losing his job, and sentenced to seven years in prison.

Faridi said he was angry because the FBI owed him thousands of dollars in unpaid expenses, according to reports of the case.

MEE understands Faridi is seeking to appeal his conviction. But he now faces further charges for talking to journalists about his career. MEE did not talk to Faridi and could not reach him for comment in researching this story.

One person familiar with Faridi’s career told MEE he had played an important role over many years in infiltrating terrorist networks and disrupting terrorist plots, and had saved many lives and faced life-threatening situations.

They said Faridi had been “completely screwed over” by the FBI for “trying to tell the truth”. An FBI spokesperson told MEE: “We have no comment.”

Source: Middle East Eye