Hezbollah terrorist group has become Lebanon’s main problem

Lebanon is in chaos. For more than a week mass protests have been blocking city streets and town squares across the country. The crowds are demanding the resignation of the government, an overhaul of the country’s political system and an end to the growing financial burdens imposed on them. Prime Minister Saad Hariri’s economic reforms package, announced on Oct. 21 has failed to placate them. For the moment, though, the prospect of the government resigning is remote, since it contains a strong Hezbollah element.

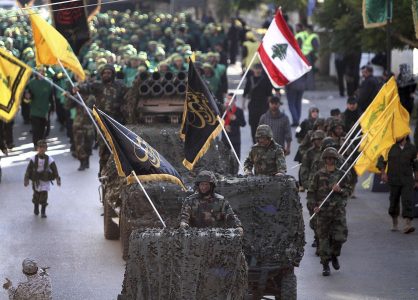

Many believe that Hezbollah, deemed a terrorist organization by large parts of the world, had created a “state within a state” inside Lebanon. Many believe that the Lebanese state and Hezbollah are in effect indistinguishable.

In theory, Lebanon should be a template for a future peaceful Middle East. It is the only Middle East country which, by its very constitution, shares power equally between Sunni and Shiite Muslims and Christians. Theory, however, has had to bow to practical reality. Lebanon has been highly unstable for much of its existence, and its unique constitution has tended to exacerbate, rather than eliminate, sectarian conflict.

How complete is Hezbollah’s takeover of the state of Lebanon? As regards the economy, Hezbollah has large investments in the Lebanese banking sector and in a wide range of businesses. On the political front, it is stronger than ever.

The country went to the polls in May 2018. The elections saw the Hezbollah-led political alliance win just over half of the parliamentary seats. A major factor in Hezbollah’s popularity – especially among Lebanon’s Shiite population – is the vast network of social services, funded by Iran, that it runs, providing healthcare, education, finance, welfare, and communications. It has virtually taken over the state’s function in many areas. The bodies providing the social provision are used to disseminate Hezbollah’s ideology and strengthen its position within Lebanese society.

The government that was eventually formed some nine months after the poll reflected the dominant position attained by Hezbollah and its allies. The organization was allocated three ministries, while the Finance Ministry went to a Hezbollah ally. Might is right in Lebanon, and Hezbollah dominates within the government because it is backed by the financial and military sponsorship of Iran. Corruption in official circles and exploitation of the population are both endemic.

The distinguished commentator on Middle East affairs, Jonathan Spyer, recently analyzed the extent to which Hezbollah, acting as a proxy for Iran, has swallowed up the Lebanese state. The shell of the state has been left intact, he pointed out, both to serve as a protective camouflage and to carry out those aspects of administration in which Hezbollah and Iran have no interest. As a result, he concludes, it is impossible today in key areas of Lebanese life to determine exactly where the official state begins and Hezbollah’s shadow state ends.

Lebanon’s March 14 Alliance is a coalition of politicians opposed to the Syrian regime and to Hezbollah. March 14, 2005, was the launch date of the Cedar Revolution, a protest movement triggered by the assassination of former Lebanese prime minister, Rafik Hariri earlier that year. The demonstrations were directed against Bashar Assad, President of Syria, suspected from the first of being behind the murder, and his Iranian-supported allies in Lebanon, Hezbollah, widely believed to have carried out the deed.

The echoes of Rafik Hariri’s cold-blooded slaughter have continued to reverberate through Lebanese politics. Hariri had been demanding that Hezbollah disband its militia and direct its thousands of fighters to join Lebanon’s conventional armed forces, a demand that leading opinion-formers in Lebanon continue to make. With Hezbollah fighting to support Assad, while a large segment of Lebanese opinion is in favor of toppling him, the conflict has inflamed sectarian tensions.

Many Lebanese, even those of Shiite persuasion, resent the fact that Hezbollah is, at the behest of Iran, fighting Muslims in a neighboring country – activities far from the purpose for which the organization was founded. They resent the mounting death toll of Lebanese fighters.

Mass unrest has shaken Lebanon before – it had its share of “Arab Spring” upheavals in 2011 – but for the first time protests are just as evident in the south of Lebanon, an area tightly controlled politically by Hezbollah, as in the rest of the country.

That Lebanon’s masses may be rebelling against the stranglehold that Hezbollah has exerted on the country is, perhaps, the most hopeful aspect of the current situation.

Source: Israel Hayom