Continuing problem in Europe’s schools is the radicalization in the classroom

For five years, Umar Haque taught children at East London mosques and secondary schools. Then he was arrested.

On March 2, Haque was found guilty of planning terror attacks at numerous sites across London, including the Parliament and Big Ben. And he’d been training his students to help him.

But Haque, who showed beheading videos, praised ISIS, and performed terrorist “role playing” scenes with as many as 250 students – some only 11 years old – is not an isolated example. As Europe braces for the return of citizens who fought with the Islamic State, some Muslim youth at home already are being radicalized, fed extremist ideologies via social media, their parents, their mosques, their teachers, and through one another. This, after all, is much of how European ISIS fighters became radicalized in the first place; and though Europe has cracked down on radical groups and imams, there clearly is far more work to do – most notably in the schools.

In Belgium, for instance, a secular primary school in Ronse reported in the spring of 2017 that some Muslim children “called others ‘pigs’ or ‘unbelievers.’ They made murder motions by drawing their fingers over their throats.” According to one teacher cited in the report, some students have stopped coming to school “because the school’s vision doesn’t fit with their beliefs,” and a toddler in her class has already been promised in marriage to a boy in Morocco. Another girl refused to stand next to boys in line.

While the school’s director downplayed the report (“we’re talking about six or so children,” he said), he also acknowledged that this is not a new phenomenon. Indoctrination and recruitment in Islamic schools and mosques has been a problem in Europe, even before 9/11. But with so many steps being taken across European and other Western countries to prevent radicalization, it is striking that, according to UK Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services, and Skills (OFSTED) Director Amanda Spielman, there are still many teachers who seek “to actively pervert the purpose of education.” Such extremist indoctrination in the UK may have already affected up to 3,000 children in over 170 “unregistered” faith schools, let alone those in schools that are licensed, the London Times reported.

Speaking at a Church of England schools conference in February, Spielman minced no words. “Under the pretext of religious belief, they use education institutions, legal and illegal, to narrow young people’s horizons, to isolate and segregate, and in the worst cases to indoctrinate impressionable minds with extremist ideology,” she said.

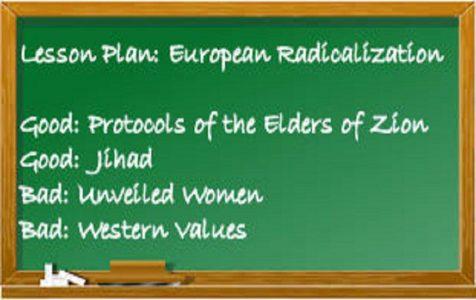

Indeed, in 2016, Sky News reported that at the Islamic Tarbiyah Academy, a primary school in Yorkshire, founder Mufti Zubair Dudha openly taught children that the anti-Semitic forgery, “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” is true; that Jews seek to “poison the thinking and minds of young Muslim people”‘ and that women should remain covered in public. He further cautioned Muslims to resist adopting British mores.

OFSTED officials also discovered extremist literature at official Islamic schools last May. Nearly a year later, at least one school, Luton’s Olive Tree, had failed to remove it all, including some books authored by an unnamed extremist described in reports only as having been banned from the UK and other countries. In a statement to the Telegraph, a spokesman defended the school claiming that OFSTED was “nitpicking” and “not very accommodating.”

Though the problems have been less extreme in the Netherlands, a number of Islamic schools have been shut down in recent years, in part because of their extremist leanings. And while teachers in secular schools have not reported the kinds of behavior seen in Ronse or England, a few have expressed concerns about students’ views. Some Muslim youth in The Hague, RTL News reports, have been known to celebrate terrorist attacks, or to show sympathy for ISIS. Teachers have also noted the popularity of conspiracy theories among Muslim students, such as the notion that ISIS is an Israeli invention aimed at turning the world against Muslims. While these ideas may originate from parents or the internet, they are exchanged freely in schoolyard conversations.

Increasingly, however, governments are starting to issue directives urging teachers to emphasize Western values. Some countries, like Germany, have also stressed the need to show respect for Muslim views that may contradict those values. As a brief from think tank network EuroMesCo put it, “it is hardly possible to demand tolerance as a learning goal if students themselves do not experience tolerance regarding their life plans.”

Yet while all concur that schools offer as much opportunity to counter radical ideas as they do to spread them, not everyone agrees with the German take. Should teachers show tolerance towards a student whose “life plans” include violence or discrimination?

In fact, France, which has faced the most brutal Islamist terror attacks in Europe most recently, is taking precisely the opposite approach. After the Charlie Hebdo killings in January, 2015, France announced a €250 million program to tackle extremism in the schools. Among other things, the program requires students to take civics and ethics classes, and to take part in annual Day of Secularism celebrations on Dec. 9.

Now, with heightened concerns about the threats posed by returnees from the Islamic State, the French government last month expanded its emphasis on education with programs aimed at training teachers to recognize the signs of radicalization in their students. Religious schools, attended by approximately 74,000 students, will come under increased scrutiny. Such schools, the New York Times reports, are often identified with the spread of radicalization.

“Nobody has the magic formula for ‘deradicalization,'” French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe said in a statement to the press. True enough. But schools would seem a good place to start: It is inside the schools that minds may be shaped for those who could become the jihadists of tomorrow. Or not.

Source: Investigative Project