Report: Climate changes will ‘fuel’ the terrorist groups

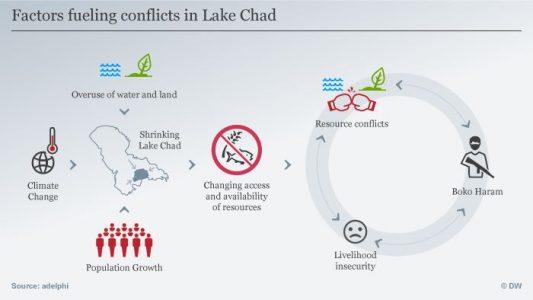

A report commissioned by the German foreign office shows how in scenarios of instability and conflict, climate change can contribute to the emergence and growth of terrorist groups such as Boko Haram or “Islamic State.”

The German foreign office has commissioned a report analyzing the links between climate change and the growth of non-state armed groups in scenarios of instability and conflict like Syria or the Chad Basin.

Co-author Lukas Rüttinger discusses its main findings with DW.

DW: You describe climate change as a “threat multiplier” – what does that actually mean?

Lukas Rüttinger: Climate change interacts with other pressures on societies and states and increases existing risks of fragility and conflict. It can exacerbate livelihood insecurity, for example, and contribute to conflicts around natural resources such as water and land.

In sum, climate change multiplies existing security risks and increases the complexity of unstable situations since environmental factors interact with social, political and economic factors.

More concretely, how is climate change connected with terrorism?

Climate change does not create terrorists or insurgents, but it does create an environment that lets them thrive and grow. In areas where the state lacks the authority or the capacity to provide security and basic services, non-state armed groups operate more freely. They use the weaknesses of the state to undermine it further.

On the other hand, the impact of climate change on natural resources such as land and water increases the livelihood insecurity of local populations, mostly of whom rely on climate sensitive sectors like agriculture. When people loose their livelihood, they become more vulnerable to recruitment by terrorist groups. These groups can offer economic incentives in terms of pay, or address grievances of local populations.

This is particularly important in local populations that feel excluded or marginalized from the government. Terrorist groups offer, for instance, prospects for youth who have no job and believe that the state does not help them.

In which way can natural resources be used as a weapon of war?

Since climate change increasingly impacts natural resources in a negative way, these resources become a valuable source of power.

Terrorist groups can control water as a tactic, by controlling water resources, creating floods or controlling critical infrastructure like dams. The “Islamic State” in Syria, for instance, tries to control rivers and water resources.

You’ve analyzed the link between climate change and violent conflicts in the Chad Basin, Syria, Afghanistan and Guatemala. What are the similarities among these cases?

Climate change acts in similar ways by creating fragility and undermining livelihood. These mechanisms create an environment in which very different armed groups can grow. Armed groups inside organized crime in Central America are very different from the Islamic State or Boko Haram – but the root causes behind them have similarities when it comes to the impacts of climate change.

So does the pattern also applies to violence outside armed conflicts?

The spectrum of non-state armed groups is very broad, including groups like Boko Haram and the Islamic State, insurgencies like the Taliban in Afghanistan, or criminal groups in Central America, where they represent important security threats.

In some Central American countries, the number of deaths these [mafia] groups create is comparable to the victims of armed conflicts in other regions in the world.

For those in Europe or North America, these problems might seem a bit too far. Why should all this matter?

Terrorists groups are actually not that far from us, and these groups have a global reach. The crises around the world, in Chad or Syria, reach us through refugees – but also, our interests around the world are affected in terms of security and economic development.

What can we do to face these threats?

At the moment [our approach to] security challenges in general, and terrorism in particular, is quite narrow. There is not a deep comprehensive understanding of the dynamics and interaction of different factors behind those phenomena. In order to devise strategies that really address and deal with them, we need to broaden our perspective and our understanding of environmental, political, economic and social factors. Solutions have also to reflect the multidimensionality of the risks.

In practice, this means that if we increase humanitarian funding in reaction to the crises, we really have to make sure that those funds are conflict- and climate-sensitive, and that they take both sides of the coin into account.

Solutions do not lie only in the security field; if we want to address these problems, we have to make sure that our development cooperation and humanitarian aid are addressing the right problems.

Lukas Rüttinger is a senior project manager at Berlin-based think tank adelphi and leads the areas of peace and security, and resources.

Source: /DW