Ancient Christian ruins discovered under ISIS garbage dump

For more than two years, ISIS forces who occupied this northern Syrian city paid little attention to the tip of an old gate on an empty mound of land where they dumped trash.

They were clueless the gate ran several feet into the ground down to something they might well have destroyed had they known: The ruins of an ancient Christian refuge, or early church, possibly dating back to the first centuries of Christendom’s existence, under the Roman Empire.

“I was so excited, I can’t describe it. I was holding everything in my hands,” Abdulwahab Sheko, head of the Exploration Committee at the Ruins Council in Manbij, told Fox News, as he led a reporter on a recent tour of the ruins.

Among the artifacts found that indicate this was a significant site for Christians were several versions of crosses etched into columns and walls, and writings carved into stone.

“This place is so special. Here is where I think the security guard would stand at the gate watching for any movement outside,” Sheko explained, working his way through what he called the “first location” of the site. “He could warn the others to exit through the other passage if they needed to flee.”

The ancient space is carved out with narrow tunnels, complete with grooved shelves to offer light, which were believed to offer passage for worshippers. There are myriad escape routes in the tunnels as well, featuring large stones that may have served as hidden doors. Also visible are three jagged steps leading up to what Sheko believes was an altar of sorts.

The discovery of a so-called “secret church,” dating as far back as the third or fourth century, A.D., could be an important find, according to a leading American archaeologist.

“They indicate that there was a significant Christian population in the area which felt they needed to hide their activities,” said John Wineland, professor of history and archaeology at Southeastern University. “This is probably an indication of the persecution by the Roman government, which was common in the period.”

Wineland said Christians were persecuted “sporadically at first, and later more systematically by the Roman government.” Christianity was illegal in the Roman Empire until its worship was decriminalized by Emperor Constantine in 313 A.D.

Christians of the time “met in secret, underground, to avoid trouble. But the Romans were fearful of any group that met in secret,” said Wineland.

“The Romans misunderstood many Christian practices and would often charge them with crimes, such as cannibalism,” Wineland added. He said such charges stemmed from the “Roman misunderstanding of Christian communion where Christ said to take and eat His body and drink His blood.”

As more of them are unearthed and studied, it’s not yet clear just how important a find these new ruins might be.

Sheko said he reached out to international archeologists and organizations since his team began cleaning up the site last fall, and needs help identifying artifacts and to “test the bones” of human remains found here. But the response from abroad so far, he said, is that it is still too dangerous to send archaeological teams to this part of a still devastatingly wartorn country.

Sheko said he’s also hopeful the Vatican will “become aware of these discoveries” and will soon send someone to inspect the ruins.

The site was fortunate to escape ISIS’ attention. Sheko said he was in the midst of studying the neighborhood when the infamously Christian-hostile group invaded in 2014. He managed to keep the secret of it quiet until ISIS was driven out in a bloody offensive by the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces in 2016.

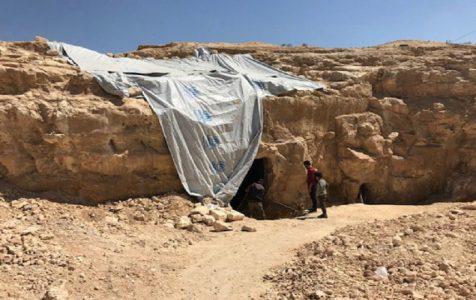

Due to the area being riddled with mines and booby traps, extensive cleanup and digging at the site couldn’t begin until late August last year. The excavation produced enough by March for Sheko and his team to host “a festival” of sorts for a handful of locals to come and visit.

In fact, it was the locals who led the way to another, very recently discovered “second location” ‒ which is still littered with insects, trash ‒ and even a stray dog sleeping inside. Within this location, down 11 jagged stone steps and into a cave that opens up into a multitude of rooms, overt Christian symbols are everywhere, etched into the stone walls and across the arched ceilings.

“We think this place after Christianity was no longer a secret anymore,” explained Sheko, gesturing to the symbols.

Wineland agreed and said he believes that, based on the photographs shown to him by Fox News, the crosses chiseled into the walls, along with geometric designs consistent with the Roman era, appear to have been added later, after wider acceptance of the Christian faith.

“That is what we would call a secondary use of the tomb, and it might well have been a Christian place of meeting or worship,” he said.

Further into the subterranean maze is a “graveyard,” Sheko said, likely reserved for the church clergy. Each tomb there bares an elevated “stone cushion” for the head.

There are still human remains inside the tombs. One local resident told Fox News he comes to visit the ruins regularly and has actually touched human bones — and watched them then “disintegrate” before his eyes.

The cleanout process for this “second location” began in September 2017, requiring seven men, digging tools and a forklift.

Sheko said there are many more potential ruins that have yet to be unearthed, but residential buildings above them makes excavation much more complicated.

For now, the sites are guarded by a young, plainly dressed 21-year-old and his AK-47. And outside of the nondescript Ruins Council office, precious artifacts are simply being left on the street, due to lack of resources for safeguarding and “no museum to put it in,” Sheko said.

These include an apparent Roman-era effigy carved into a limestone building block, grave markers, arch fragments and column bases. One has a Greek inscription on an architectural block.

“Greek was the common language of the Eastern Roman Empire, which explains why the New Testament is written in Greek during the Roman period,” Wineland said.

Hassan Darwish, the council’s field monitor responsible for archiving and topography, also noted they have managed to salvage some key pieces discovered by ISIS and sold off in local markets. These include ages-old mosaics, some of whose faces were destroyed by ISIS before being pawned off.

Manbij, located in northeastern Aleppo Governorate near the Turkish border, and 18 miles west of the Euphrates, was long considered one of Syria’s most ancient and prized townships. Given the area’s prominence in the centuries following Christianity’s founding, archaeologists believe more Christian sites could be unearthed in the areas liberated from ISIS.

Most of the land encompassing modern-day Syria was annexed in 64 B.C. by the Roman Republic. For centuries it was a crucial center for trade and commerce in the Eastern – or Byzantine ‒ empire.

By the seventh century, however, Islam began to spread through the Arab conquests, and Syria eventually became overwhelmingly Muslim.

At the start of the civil war, Christians made up about 10 percent of Syria’s population.

Wineland said the recent discoveries reminded him of the intense persecution of Christians in modern-day Syria and Iraq. “This has led to a significant decline of Christians in the region. Some have been killed, others have fled, and still others have been coerced into converting to Islam.”

Despite Christianity’s difficult history in Syria, however, Sheko said he wants to make clear his commitment to unearthing and protecting whatever ruins he and his team might find.

“We are Muslim, but we are not like ISIS Muslims,” he said. “We take care of these Christian ruins. We respect them. We respect humanity.”

Source: NYP