Al Baghdadi’s brother travelled in and out of Istanbul as his courier for months

A brother of ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi travelled several times to Istanbul, Europe’s largest city, from northern Syria in the months before the terror chief’s death, acting as one of his most trusted messengers to deliver and retrieve information about the group’s operations in Syria, Iraq and Turkey, according to two Iraqi intelligence officials.

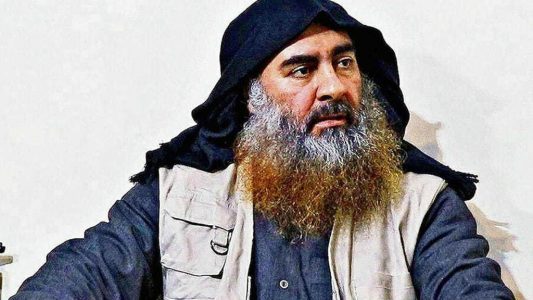

The hunt for the elusive architect of ISIS, a man once known as the “invisible sheikh”, concluded on October 26 in a dramatic, covert US special forces raid on his isolated villa in the north-western Syrian border village of Barisha, in Idlib province. He killed himself by detonating his explosive vest when backed into a tunnel with no escape, US President Donald Trump said.

Now, The National can reveal new details about the movements of one of the key members of Al Baghdadi’s inner circle and how he made several 2,300-kilometre round trips deep into the territory of a Nato member, the terror chief’s use of an old-fashioned militant method to evade detection while directing the group from the shadows and the joint efforts of Western and Middle Eastern security services to catch a trail that could lead them to one of the most wanted men in the world.

“We were watching somebody who was acting as a messenger to Al Baghdadi and he was travelling frequently to Turkey and back,” said a senior Iraqi intelligence official. “He was Al Baghdadi’s brother.”

That brother was Juma, one of Al Baghdadi’s three male siblings, who is still believed to be alive. Iraqi security services first detected him crossing the Syrian-Turkish border at the end of 2018 before he appeared in Turkey’s largest city, where ISIS militants or sympathisers have attacked a nightclub on New Year’s Eve, tourists in its historic Sultanahmet Square near Hagia Sophia and its now-closed Ataturk International Airport.

Iraqi security services worked in collaboration with their American counterparts on the surveillance of Juma inside Turkish territory, the officials said. Spokesmen for the Pentagon and US-led coalition to defeat ISIS said they would not comment on matters of intelligence. The office of the Turkish presidency and the Turkish interior ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

An Iraqi intelligence agent who worked directly on the operation to track Juma said the terrorist leader’s brother continued to reappear in the following months, until his last recorded visit to Istanbul in April. He is then believed to have returned to north-western Syria, months before the location of his brother’s safe house was revealed. It is unlikely he was smuggled across the border, the agent said, but rather moved across it freely.

The Iraqi operatives cultivated an asset in Istanbul who would become privy to details about Juma’s Istanbul trips and what was exchanging hands on behalf of Al Baghdadi.

“Juma, the brother of Al Baghdadi, was in contact with a guy in Turkey who was meeting our source inside Turkey,” said the agent, who dealt directly with the handler of the asset. Juma made “multiple visits” to Istanbul to meet that contact, the agent said.

The source met with a courier who would hand packages to an appointed middleman. That intermediary would then pass the packages on to Al Baghdadi’s brother for delivery to the leader in northern Syria, according to the agent.

The contents of the packages exchanged in Istanbul reveal how Al Baghdadi persisted in directing the group and the lengths he went to remain abreast of its progress without detection even after years in hiding and months after the loss of all of the Syrian and Iraqi cities the group had once controlled.

“He was delivering messages from ISIS commanders in Iraq. The state of their forces, money, logistics, routes,” the agent said of the courier. “[He] was in contact with commanders here [in Iraq].”

But it was not only Iraq in which Al Baghdadi showed an interest. On these trips, Juma was tasked with “passing on messages and bringing messages back and forth to the ISIS guys inside Turkey”, the senior intelligence official said.

Even though the Iraqis and the Americans conducted joint intelligence work on tracking Al Baghdadi’s go-between for five months, the official said, it remains unclear if he was handing Al Baghdadi the packages in person after receiving them, and if that was done in Idlib. That is because they would lose track of him when he entered into the extremist-laden Syrian province where Al Baghdadi was eventually found.

The officials became confused as to why his trail would end in Idlib, as they believed Al Baghdadi was hiding in the eastern Syrian province of Deir Ezzor, and they wondered how his brother could transit territory held by the Syrian regime or the Syrian Democratic Forces, the Arab-Kurdish coalition that led the ground fight against ISIS, to deliver messages to him.

“We tracked him going across the border but then we were losing track. From Turkey he travelled south through Idlib but it seems like he never travelled further down,” the senior intelligence official said.

“Now, we think that he just came across five clicks away from the border to meet Al Baghdadi. We don’t know if the Turks knew this or not.”

It is believed Al Baghdadi moved to Idlib in spring, around the time of the offensive to wrestle Baghouz, ISIS’s last pocket, from its remaining fighters. But the Iraqi claims indicate he could have moved there before then, or somewhere closer to Idlib and further away from eastern Syria than previously believed.

Little is known about Juma. No picture of him is publicly available nor are details of his appearance, age, current whereabouts and even his last name. As efforts to track his movements continue, much of the information about him remains classified. US special forces captured two men in the Barisha raid on Al Baghdadi’s compound, but it is unclear if Juma was one of them, or if he was present at the safe house at the time of the mission. The Iraqi officials said they do not have clear identification of who was killed or knowledge of who was captured in the raid, which was carried out by Delta Force commandos.

The brother, a member of the same pious Sunni Muslim family from the Iraq city of Samarra that sits on the east bank of the Tigris, practised an ultra-conservative version of Islam rooted in ISIS’s ideology even before Baghdadi, Abu Ahmad, a former associate of the notorious ISIS leader, said in 2015. At one point, he is believed to have become Baghdadi’s bodyguard and was the closest to him out of the three brothers. But the account of the officials reveals that, at least in recent months, he served instead as a conveyor of Baghdadi’s orders to key ISIS figures in Turkey and Iraq.

His methods of travel from northern Syria to Istanbul and back, and the route he chose to take, remain unknown. But the ability of one of the most senior members of ISIS to commute to a major European city freely to meet other ISIS members will again raise questions about the Turkish security services and what they knew about Al Baghdadi’s final months and the movements of his closest associates, former Turkish security officials and counter-terrorism experts said.

Accusations levelled against Ankara have not been supported by hard evidence, but many in security circles point to a passive attitude in the Turkish security apparatus towards ISIS that has allowed them to build sophisticated networks inside the country.

The government is facing criticism after Al Baghdadi was found so close to the Turkish border, and it stands accused of emboldening ISIS with its offensive against the Syrian Kurds in north-eastern Syria using rebel proxies accused of potential war crimes. That offensive, which Ankara started to quash what it says is a threat of terrorism from Kurdish militants, has displaced hundreds of thousands of people.

“It is impossible for the Turkish intelligence that Turkey does not know of his presence five to seven kilometres away from the Turkish border,” a former high-ranking Turkish military officer said.

Turkey on Tuesday said it had captured Al Baghdadi’s 65-year-old sister, Rasmiya Awad, near the Syrian town of Azaz. But former officials said she likely had little to do with the group’s operations and it was an attempt by Ankara to appear to be working against the group in the face of criticism.

“For the Turkish National Intelligence, or Turkish police, [ISIS] are not the real enemy,” said Ahmet Yayla, a former Turkish counter-terrorism police chief and now a fellow at the George Washington University Programme on Extremism. “They do not seriously look for these people, but [President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan is in a position where he is trying to prove that he is fighting against ISIS.

“That is the reason they are bragging about his sister who is 65 and most probably doesn’t have much to do with the issues there or what he is doing, but they are making a huge propaganda of it in the Turkish media.”

One theory about Al Baghdadi hiding only kilometres from the Turkish border is that he was trying to move his family to the country. “This is not unknown among Islamic State officials and leaders,” according to Aymenn Al Tamimi, a prominent researcher on the modus operandi of Syrian extremist groups.

On Juma’s apparent freedom to travel, Mr Yayla expressed reservations that someone so close to Al Baghdadi could have made such a long journey to Istanbul to deliver or retrieve messages without being detected, or had chosen it as a location for meetings instead of closer Turkish border cities like Gaziantep or Sanliurfa.

“How come Turkey did not stop this person? It just doesn’t add up,” said Mr Yayla. “It is risky for someone like him to go to Istanbul. This is a strange world, anything can happen, but I wouldn’t expect such a crucial mistake from someone like him.”

Yet Istanbul may have offered a more likely location for ISIS’s senior leadership to remain undetected compared to well-known extremist hotbeds in southern Turkey.

“Istanbul has always been a relatively safe area to travel. There are many refugees. It’s easy to get lost in the crowd,” the Iraqi agent said.

In a city of at least 15 million people, “you can expect a degree of anonymity”, said a former Western intelligence chief. “You’re not under scrutiny – everybody is there.”

In smaller, southern hubs such as Gaziantep, it “would be much harder to be sure that you weren’t being followed or spotted”.

For a Syrian, Iraqi or someone of similar appearance who doesn’t have a criminal record and who has the right papers, travelling through Turkey “is not a big problem”, said Guido Steinberg, senior research associate at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and former counter-extremism adviser to chancellor Gerhard Schroeder.

“Although it’s a thousand kilometres, for the Turks it’s not considered to be a long distance. You enter the bus and that’s it. You’ve got direct connections to Istanbul from every city.”

In Turkey, ISIS has a leader of its Emni intelligence service, responsible for the group’s foreign operations, and thousands of supporters developing networks that have made it easy to move people and money throughout the country, Mr Yayla said. So, it may have made more sense for Al Baghdadi to use another lieutenant for the job.

But Juma became “one of the few people trusted by” Al Baghdadi, according to the Iraqi agent. As ISIS’s territory and leadership figures began to dwindle, so did Al Baghdadi’s reliance on his remaining commanders and foot soldiers, figures who may have arrived in Iraq or Syria only six years ago.

“It seems clear now that towards the end, Al Baghdadi only trusted some very close family members,” said Amarnath Amarasingam, an expert on ISIS and senior research fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue in London. “It also seems to be the case that key pieces of info that led to his capture also came from the people he placed his trust in towards the end.”

Even though he was being traced by other security services, Juma’s limited profile could have helped him to evade detection by Turkish security services while travelling through the country, said Colin Clarke, senior research fellow at the Soufan Center.

“I assume they have the family network mapped out but it’s not Al Baghdadi himself. So how well known were his relatives? What did he look like?”

The trailing of Juma did not lead to Al Baghdadi’s attempted capture. An informant cultivated by the Syrian Kurds inside Al Baghdadi’s inner circle and several crucial arrests of his associates would prove to be his downfall. But the tracking of Juma reveals yet another strand of intelligence that security services were following in the hope of capturing Baghdadi.

The use of a courier is a tried and tested terrorist method of evading detection, one of many used by extremist leaders in a bid to operate under the radar to continue their activities. It was one mastered by former Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who would send confidants long distances with USB drives to internet cafes to pass on information. Since then, militant evasion tactics have moved from email drafts to secure email services and on to encrypted messaging apps such as WhatsApp, Telegram and Signal.

Al Baghdadi became obsessed with secrecy, turning to handwritten notes or even word of mouth to send messages, and at times dressing as a shepherd, according to his detained brother-in-law Mohammed Ali Sajit, who gave an interview to Al Arabiya last week. Those who visited him were on occasion blindfolded on the drive to his location, while others were forced to remove their wristwatches and hand over their phones. Going dark, like bin Laden did for 10 years, can be easy, but terrorist leaders come unstuck in their failure to reconcile their need for stealth with their need to communicate as heads of these organisations, says Jason Burke, an expert on extremism.

“You can go off grid and stay off grid, but it’s difficult to communicate,” he said. “Those who are looking for you are basically guessing. But if you need to trust somebody [to courier], they are going to be identifiable.”

Yet the Iraqis and Americans did not move on Juma. They hoped he would lead them to Al Baghdadi’s location, the same way that bin Laden was tracked to his Abbottabad compound in 2011.

“In this case, the brother would not have been the target, he was just a means to the target. I think it’s entirely understandable that you might let him run and see what turns up,” said the former Western intelligence chief.

“Then, you can go on from there and see what he was doing at either end.”

Even though this was the decision in the case of Juma, the ease with which he crossed into Turkey, like many lower level ISIS members before him, will likely give Western and regional security services cause for concern, whether Ankara had knowledge of his trips or not.

“When you cook pasta, you drain it in a colander,” said the former Turkish general. “Turkey’s borders have unfortunately been like this for a long time.”

Source: The National